THE LIGHTNING SHOULD HAVE STRUCK ME

Recent Works by Arindam Chatterjee

The lightning of revelation should have struck me, not Moses on Sinai.

Make sure the drinker can hold it, before pouring him a drink.

– Ghalib

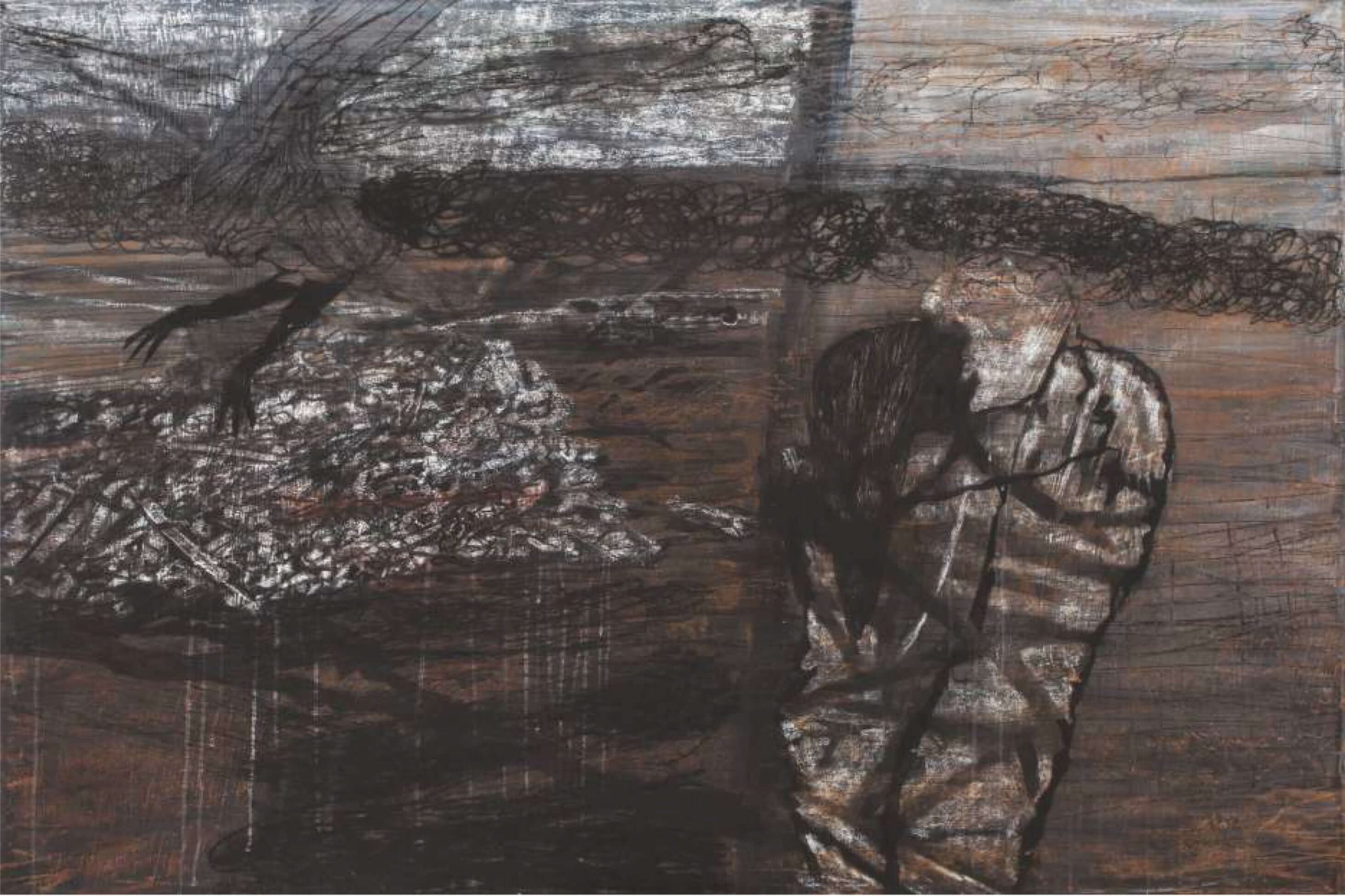

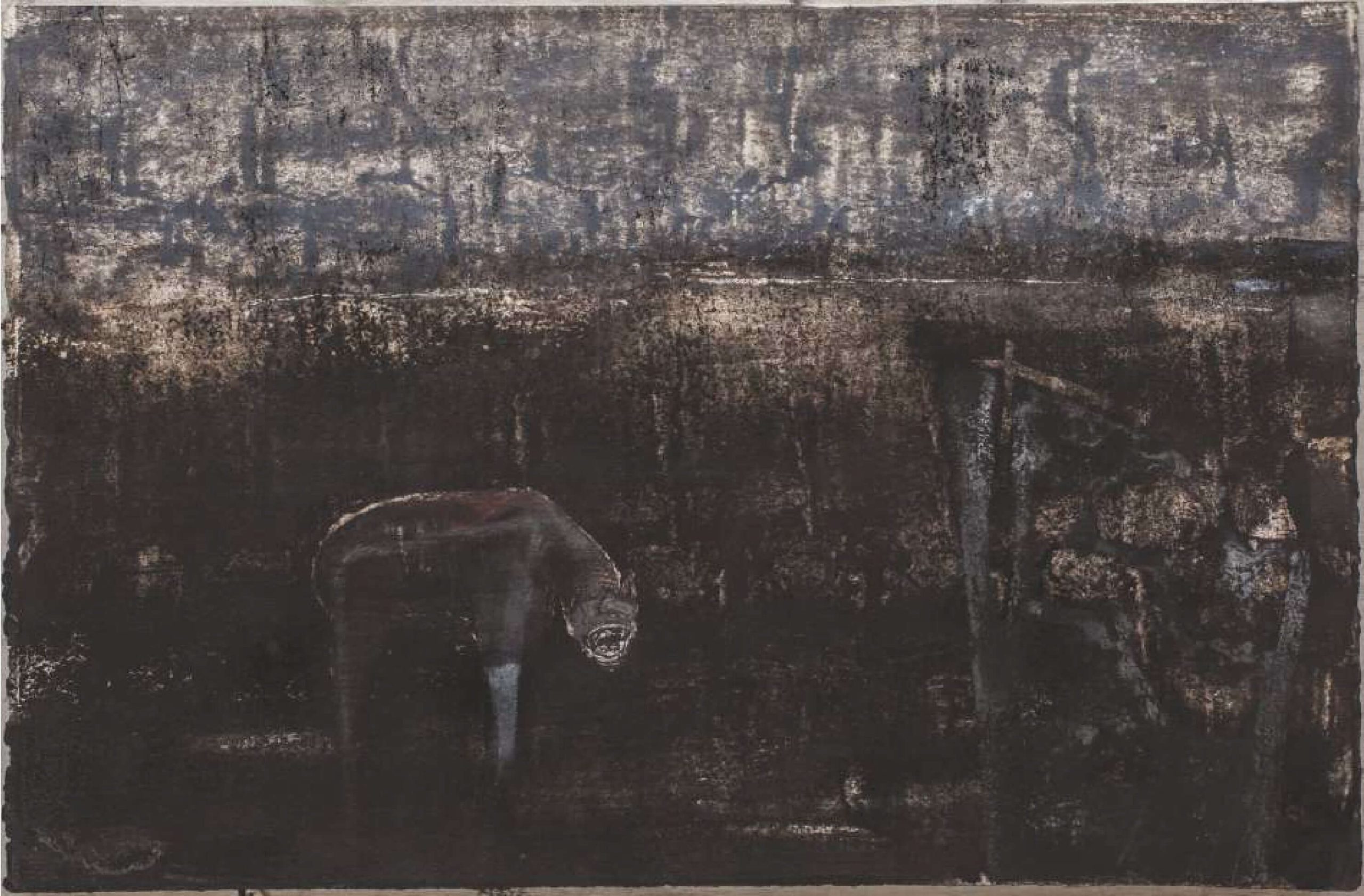

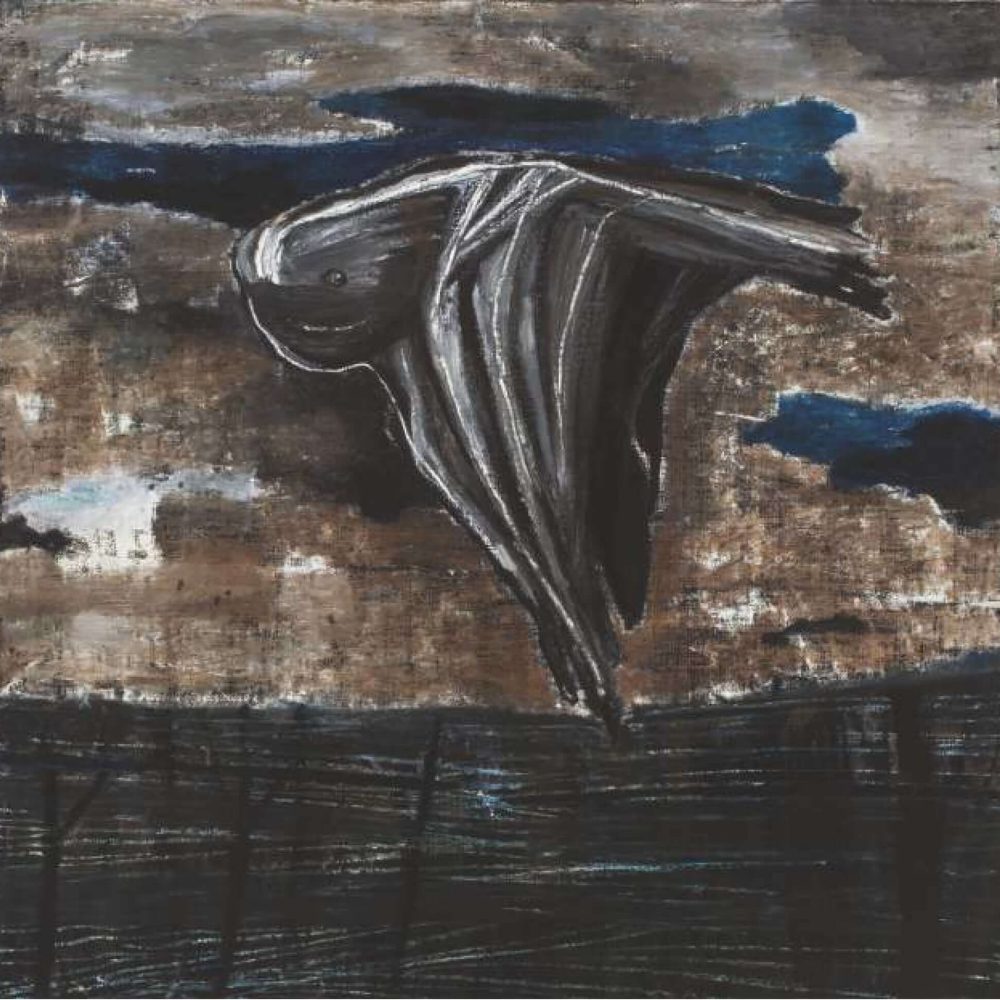

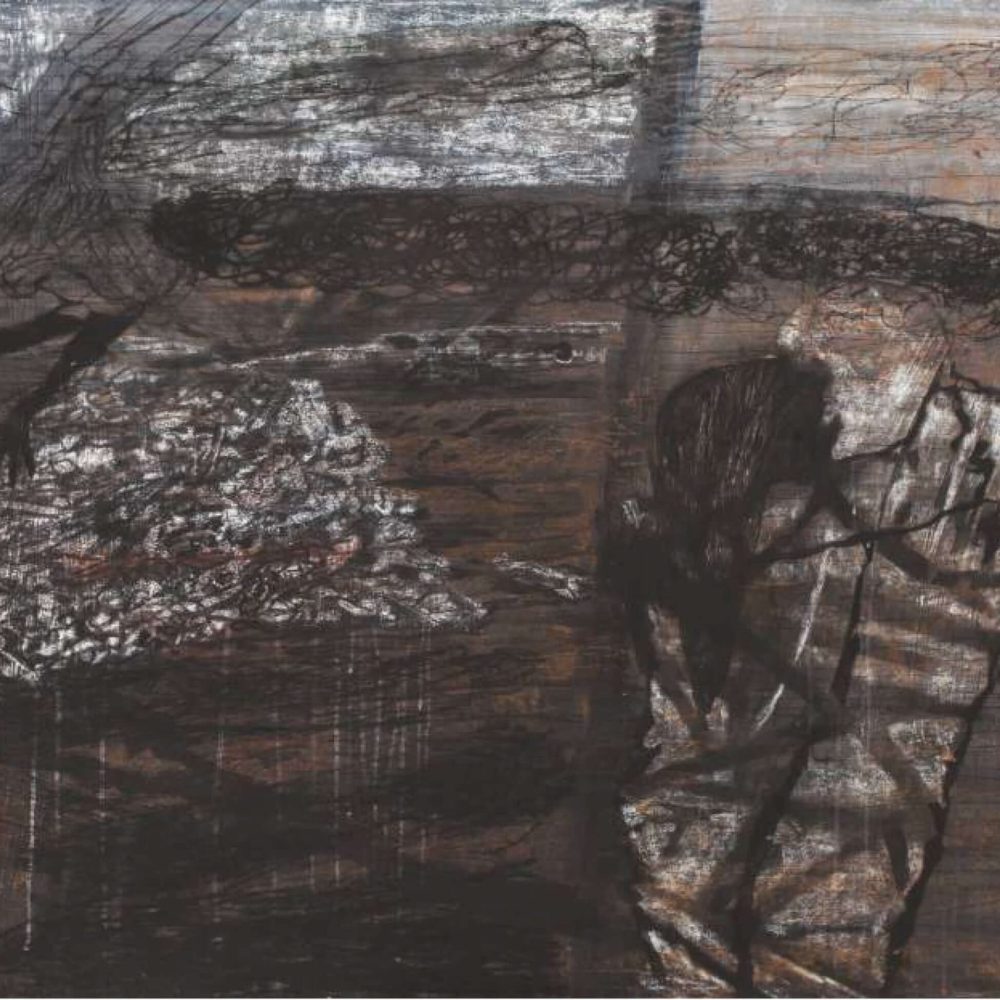

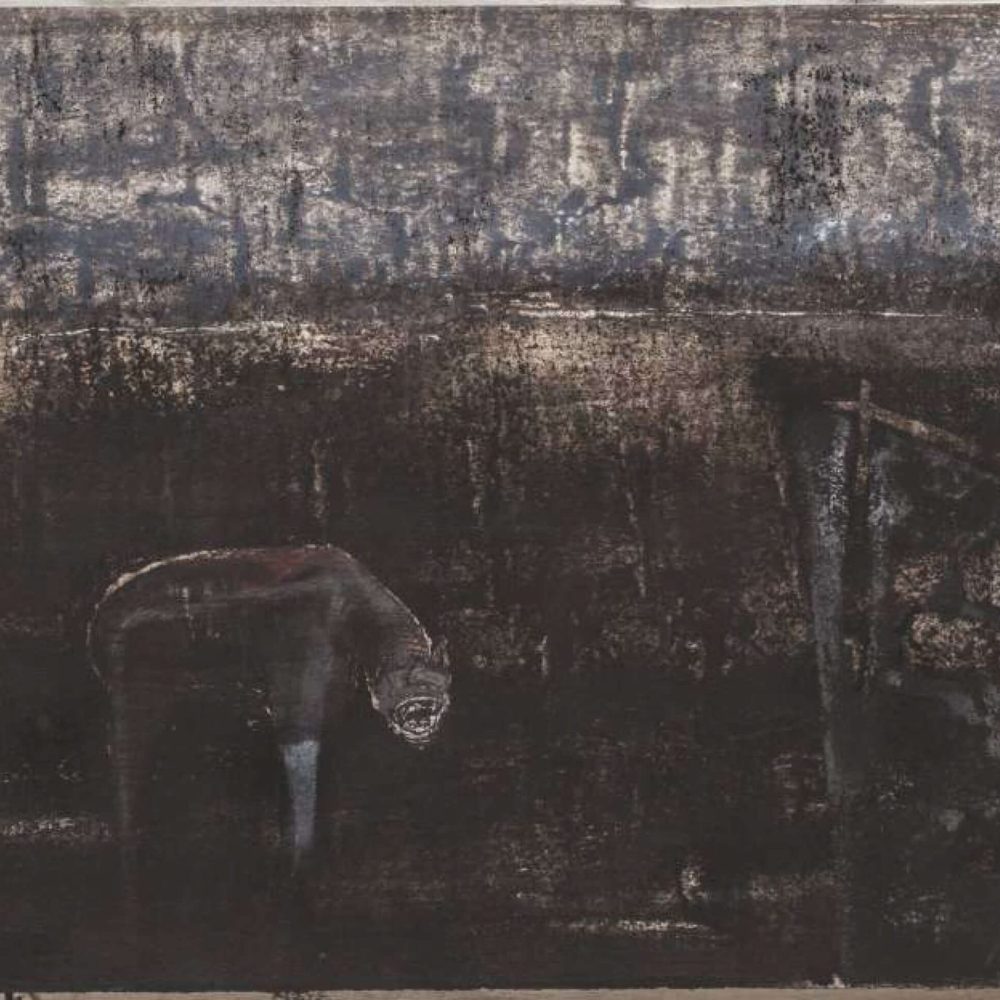

Arindam Chatterjee proposes a powerfully dystopian vision of the world, and of humankind’s place and destiny within it. Chatterjee’s paintings, drawings and mixed media works are alive with surging currents and eddies of energy that course across the surface, cloud formations electric with unease, and figures that manifest themselves in various moments of bewilderment, captivity or defiance. These works introduce us to devastated landscapes or austerely delineated spaces of captivity or quarantine. Some of Chatterjee’s frames are occupied by single figures, human or composites of human and animal; elsewhere, the artist dwells on the predicament of humans and birds locked in thwarted dialogue, or the tragedy of a fallen human and an animal helpless to intervene; occasionally, he fixes his sights on pairs of animals.

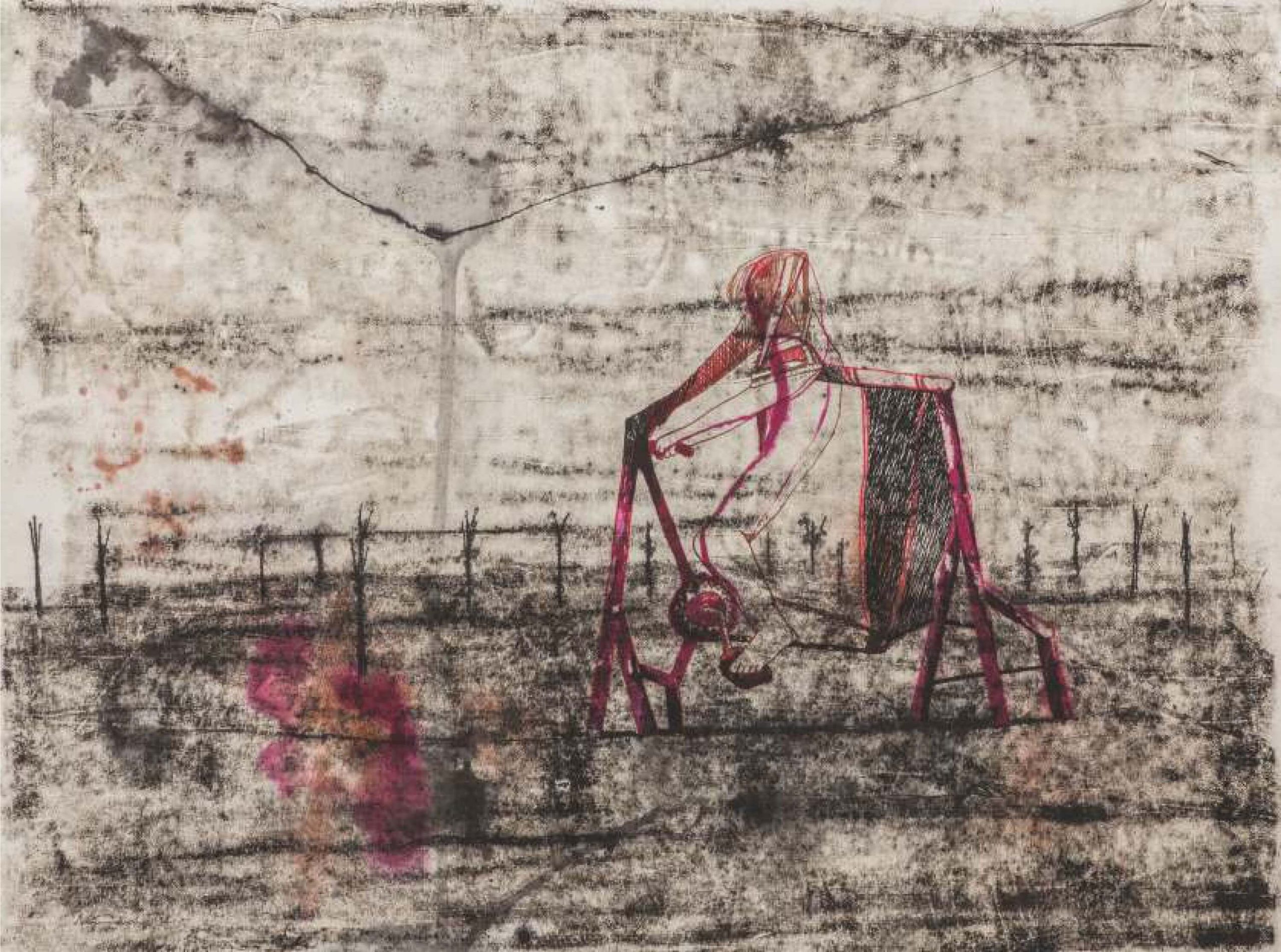

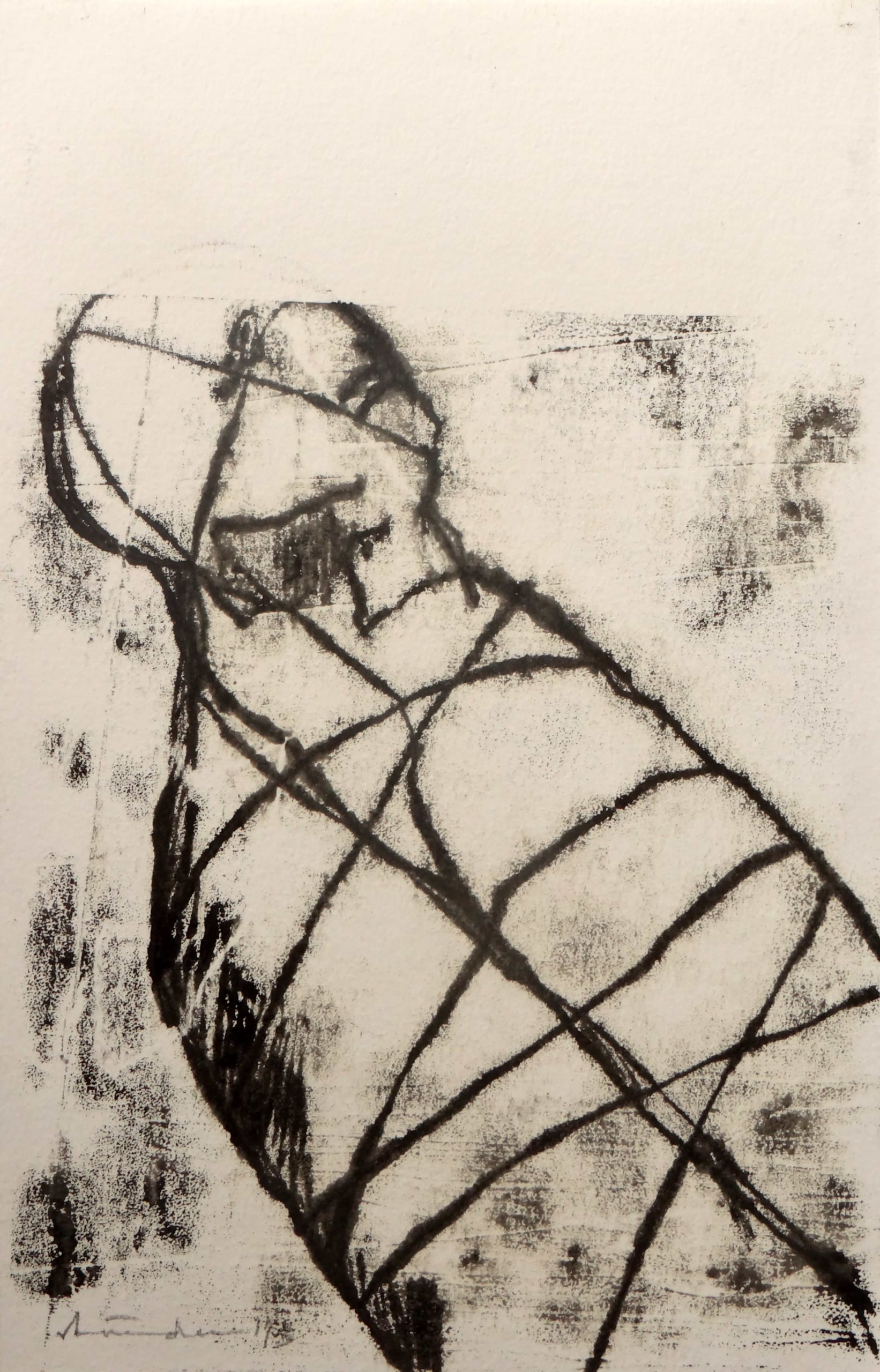

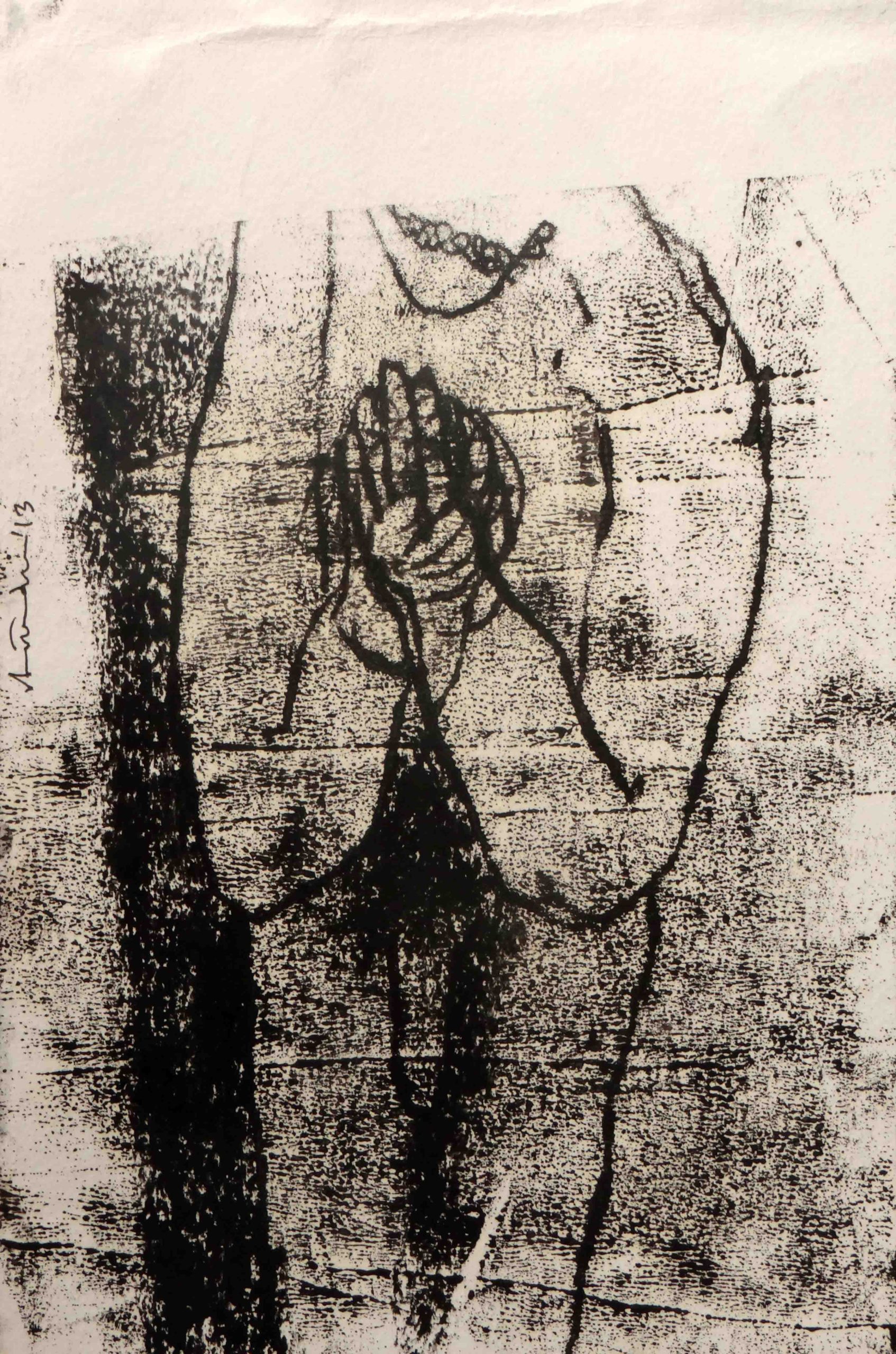

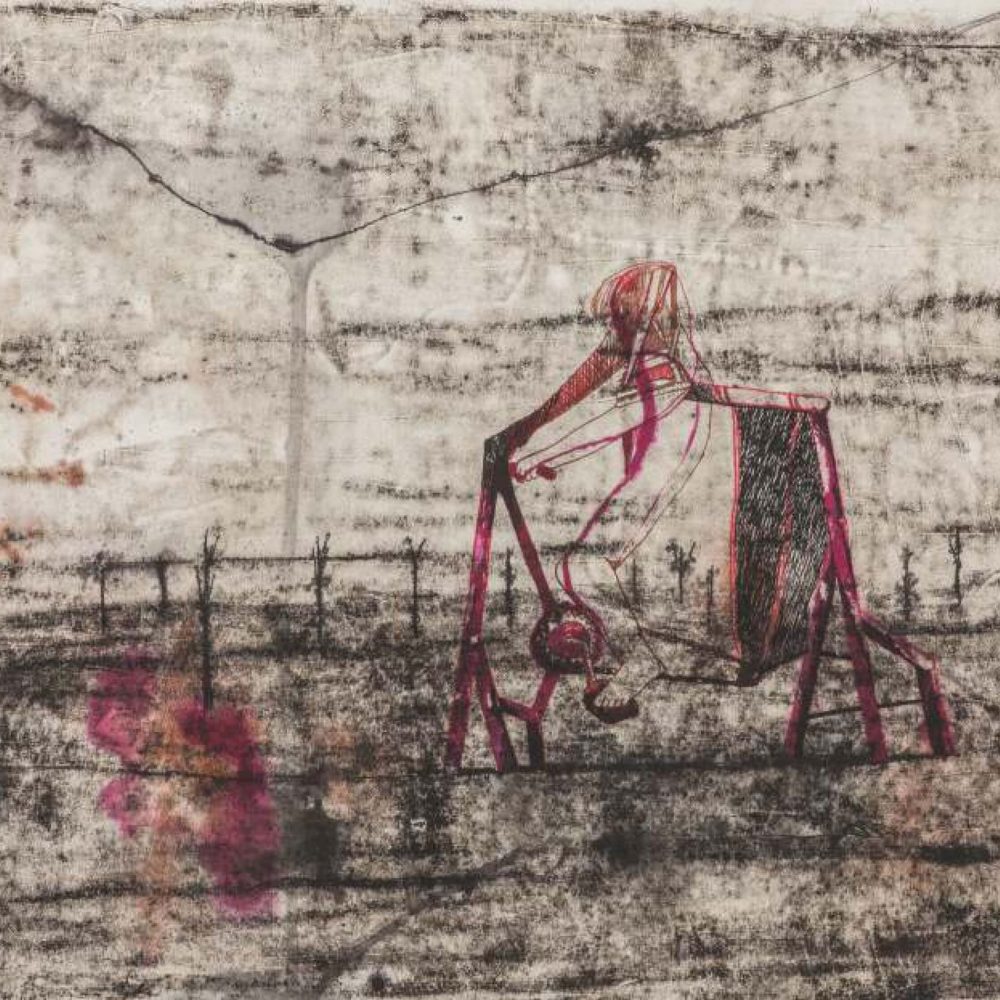

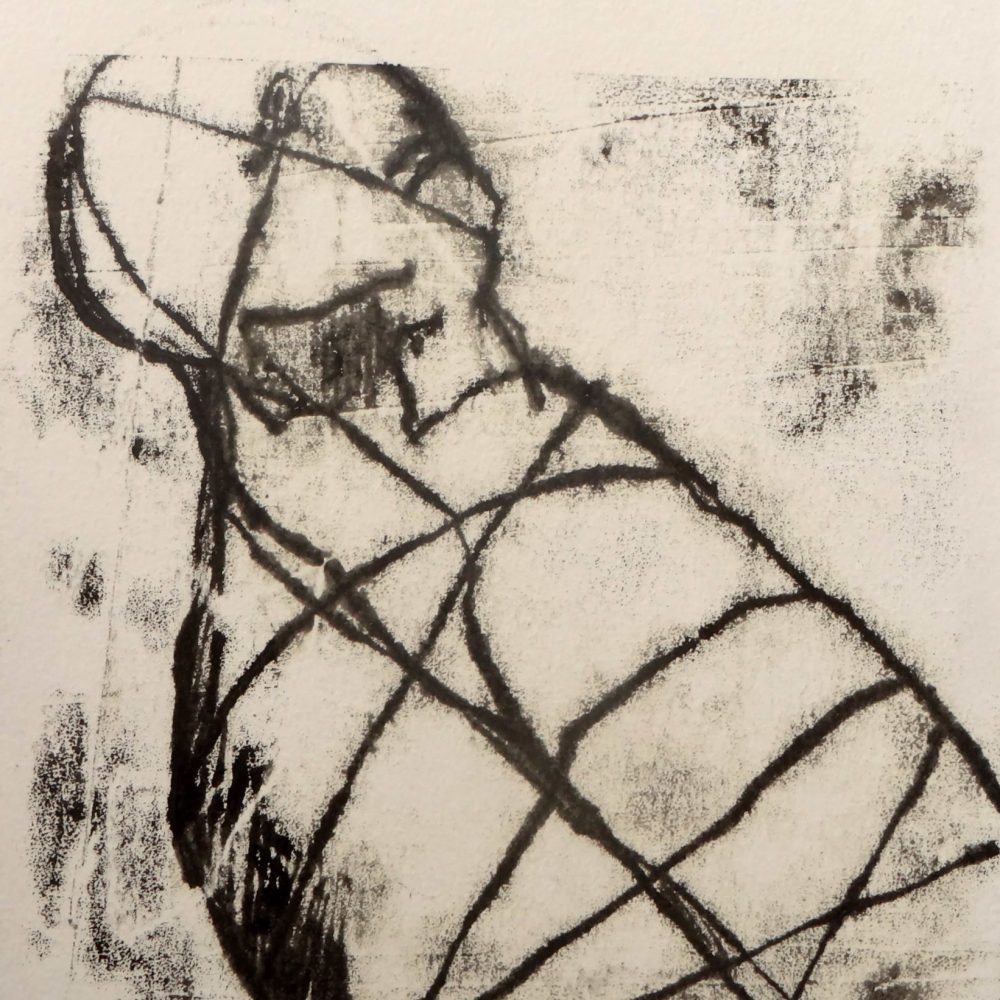

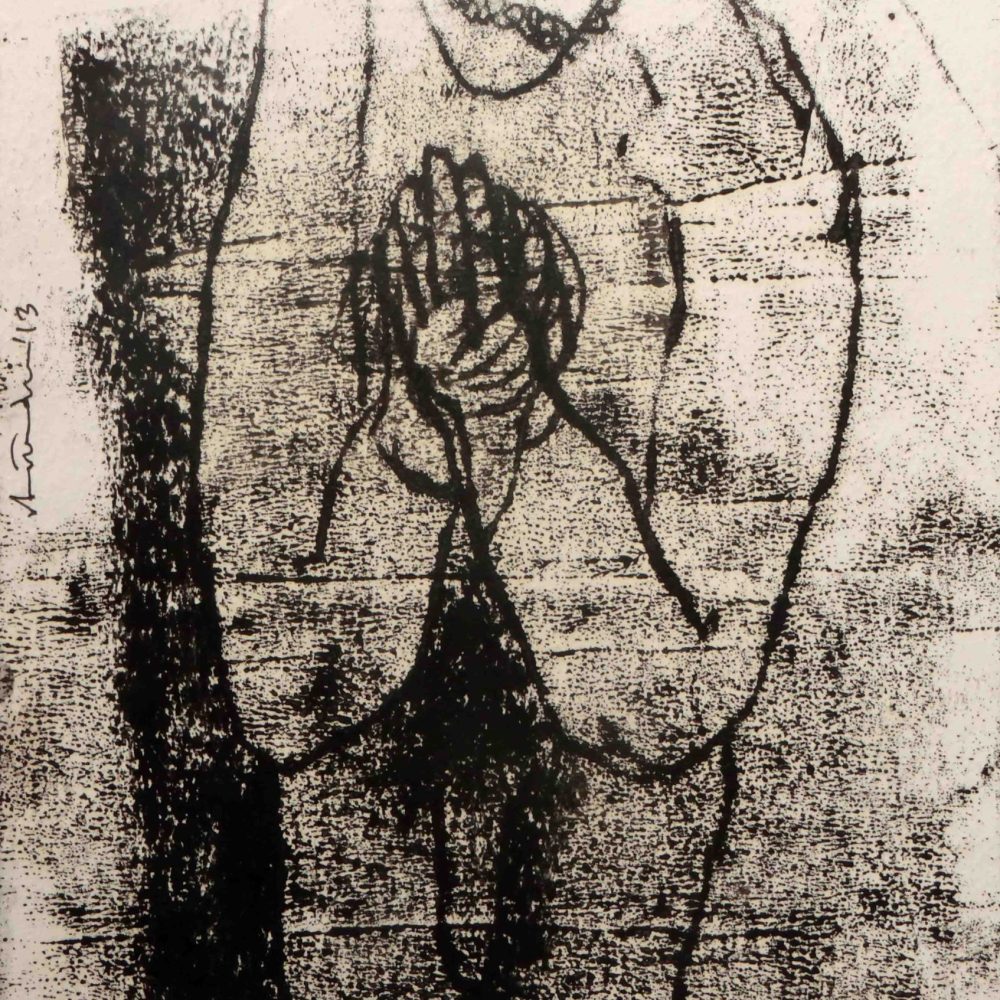

Read MoreWe confront foraging, snarling or mating beasts in Chatterjee’s bestiary. Or we reach out in empathy to trapped humanoid figures, angels reduced to scarecrows as they give voice to their anguish in minefields, gazing skyward while clamped to a fence that has become a second body, or sometimes pedalling away at futility machines that will never translate effort into movement. In Chatterjee’s idiom of figuration and his emphasis on the fundamental woundedness of humankind, we may discern the ancestral presence of Somnath Hore.

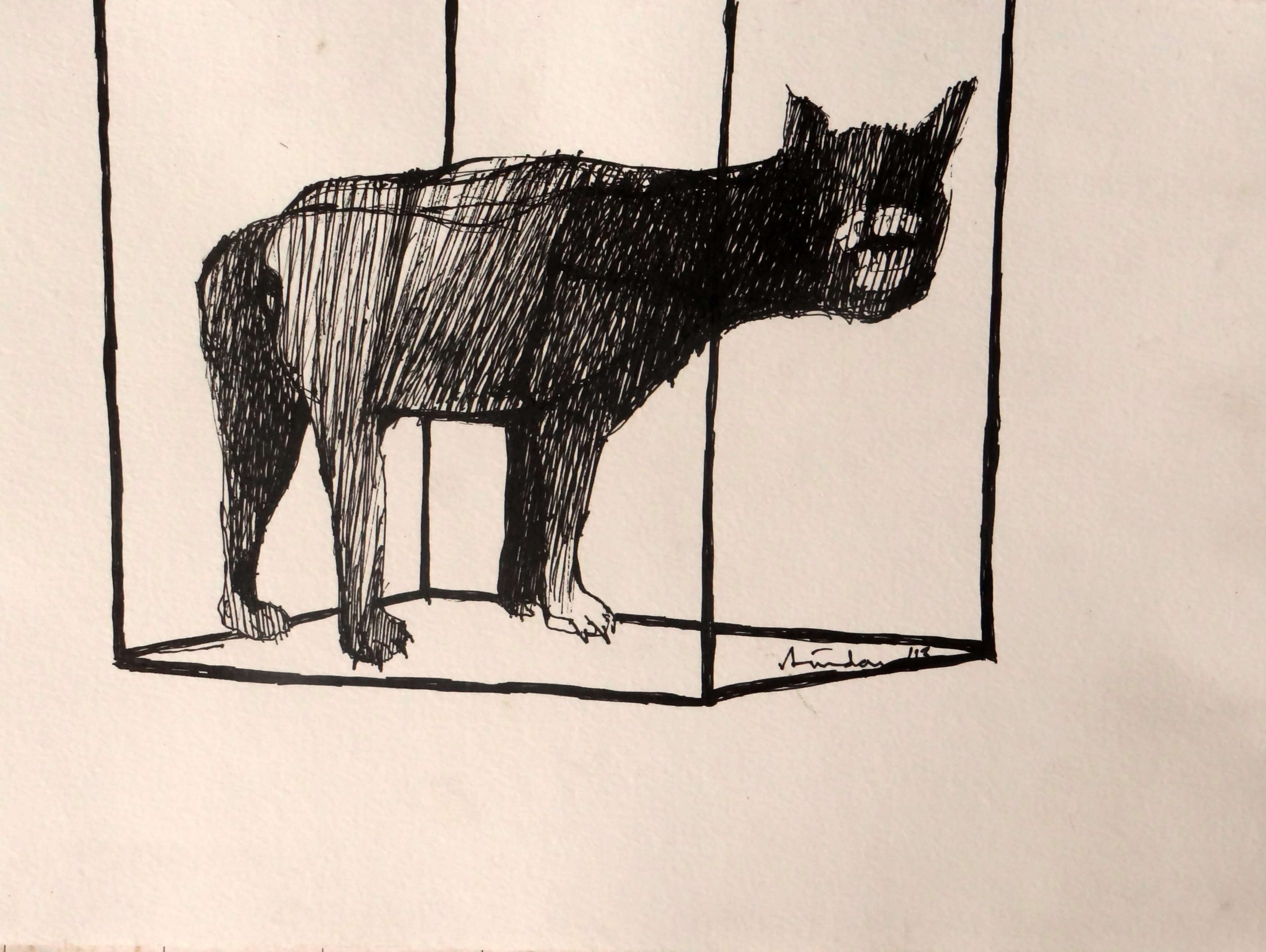

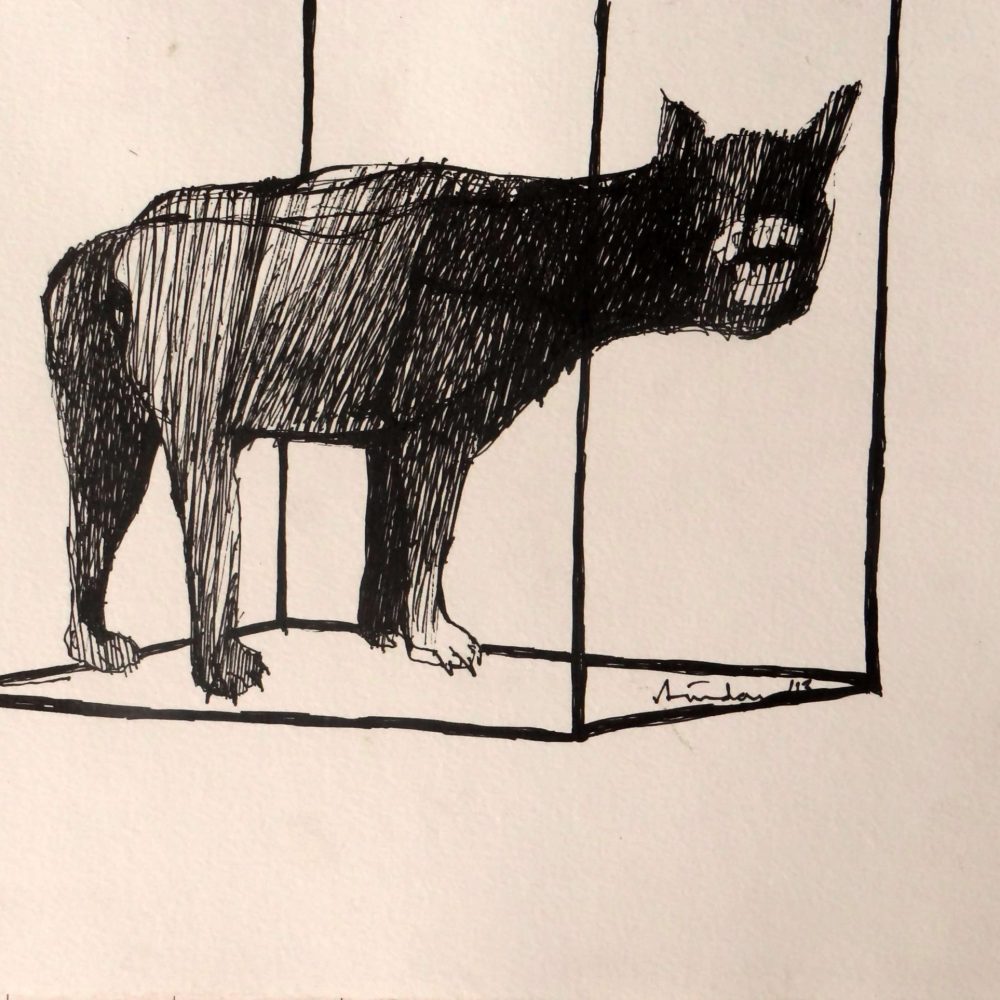

Chatterjee’s universe is a theatre of dark forces that attempt to subjugate the individual’s will and desire; against the machinations of these forces, the individual must make a courageous stand, assert herself or himself as a survivor. In some of his works, great spectral birds descend on fields that appear to have suffered battle more often than they have borne harvest; their predatory beaks strangely vulnerable when they open like wounds, these birds cry out in the sleep of Chatterjee’s protagonists. Animals, often composites of wolf and dog or allotropes of cattle, negotiate a cage or a precarious dais: their memories of expanse firmly at odds with their experience of incarceration, they symbolize the spirit of the individual, who is heir to the amplitude of emancipation but who is also, in Rousseau’s memorable formulation at the beginning of <span “>The Social Contract, “everywhere in chains”.

While Chatterjee’s diagnosis of the contemporary moment may appear bleak and his prognosis for the future is certainly a demanding one, his works are characterized by a pleasure in formal richness and an admirable appetite for experimenting with diverse combinations of media. Not only does Chatterjee demonstrate a willingness to address and articulate such grand philosophical and existential themes as melancholia, isolation and oppression, but he has also developed a sophisticated array of artistic strategies to shape his ideas and images into compelling and persuasive visual propositions. Paradoxically, therefore, we may take visual and sensual pleasure in his works, even as we are plunged into pensive introspection by them.

In his palette, Chatterjee delights in greys, dusty whites, browns that straddle the spectrum from ochre to burnt sienna, and a gamut of blacks that range from the emphatic to the misty. The palimpsest and the pentimento are vital devices in his art: each of his works acts as a palimpsest, with layers of treatments laid over one another; each of his works, also, encrypts a plurality of beginnings, traces of several episodes and trajectories that find tenancy within the same broad scenography of events. In approaching Chatterjee’s accomplished works, the viewer must act both as surveyor and as archaeologist.

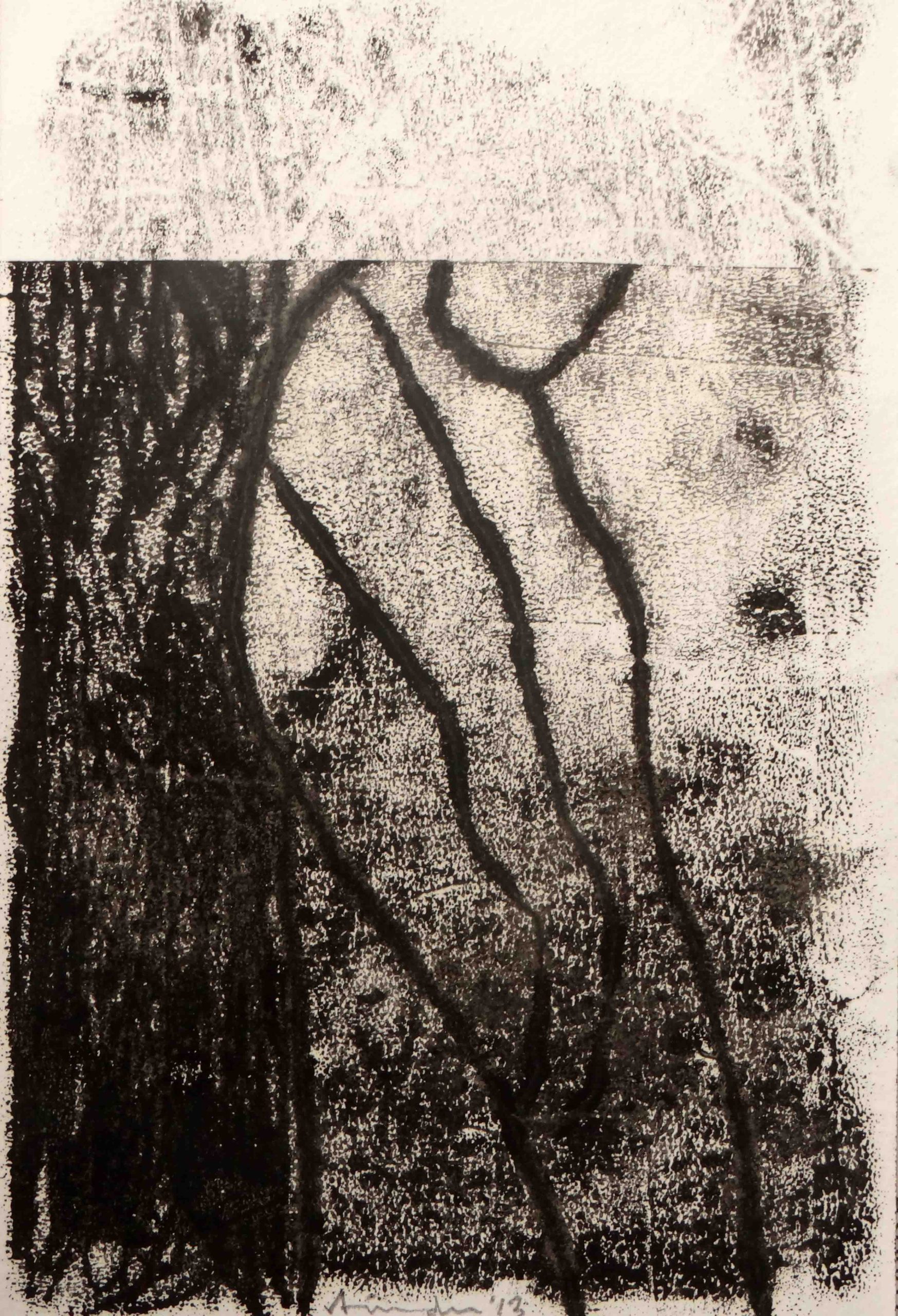

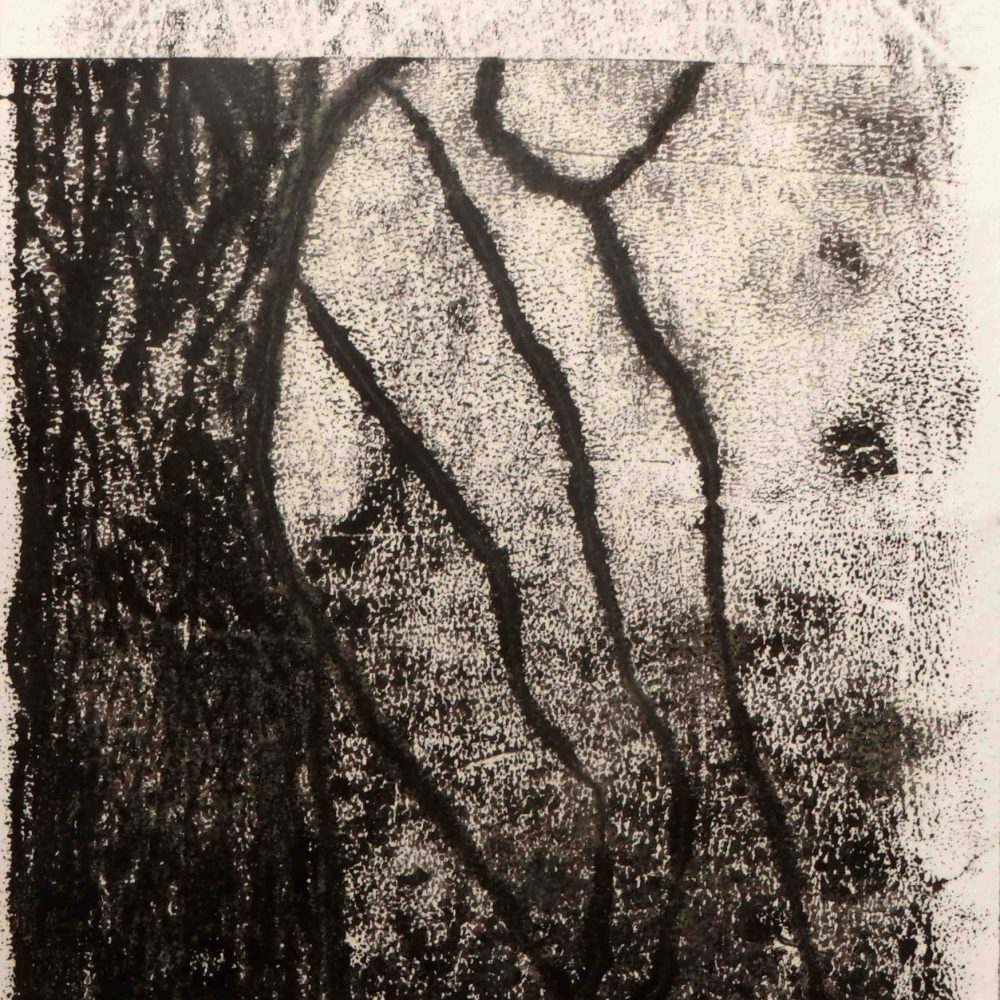

Chatterjee’s studio is evidently in the nature of a laboratory, a site where he tests out the interplay between ink and charcoal; where he coaxes oil and acrylic to collaborate with pastel and graphite; and where he considers the effects of depth and immediacy to be gained from orchestrating a choreography of conté and printer’s ink. Frottage, the memoirs of other surfaces imprinted or registered on a surface, imparts a multiplicity of textural associations to a number of his works; sometimes, also, he focuses on a single medium and produces a surpassingly pellucid watercolour; at other times, he uses the mono-print as a launch pad for departures made through the use of multiple media.

Chatterjee’s work puts me in mind of a couplet from one of the legendary Urdu poet Ghalib’s most beautiful and irreverent ghazals, which begins: <span “>“Girni thi ham pe barqe tajalli na Tur pe”<span “>. I have used my own translation of this couplet as the epigraph to the present essay. In succinct words, the poet asserts his wish that God should have blessed him, and not the prophet Moses in contemplative retreat on Mount Sinai, with the illumination of wisdom, the gift of revelation. The playfulness of this utterance and a refusal to cloak his feelings in conventional piety and sanctimony, even at the cost of irritating the orthodox, are classic elements of Ghalib’s style and world-view.

This late-Mughal poet, who was also the emperor’s literary tutor, often entered into disputation with the Divine in his poetry; such a tendency would undoubtedly have earned Ghalib the wrath of a censorious State as well as attracted the rage of the howling mob today, given India’s unfortunate and precipitous descent into illiberalism in recent decades. Indeed, Ghalib’s couplet spells out an avant-garde position for the artist as explorer of the mind’s passions who is ahead of the general consensus and opposed to it, a manifesto for the artist as custodian of a wisdom that is not identical with the common sense that society at large prizes and imposes.

When the artist takes up an adversarial or critical role, s/he runs the risk of being a prophet without a following, a teacher without disciples. Besides which, the news that the adversarial or critical artist brings down from the mountaintop may not bring comfort or consolation to those receiving it. The price that one pays, when one is a pioneer of illumination, is the indifference or hostility of one’s early audiences. In this sense, Chatterjee’s works provide elaborate and extended testimony to his own specific predicament as an artist, even as they engage with wider existential crises that afflict all humankind.

From that testimony, it is equally clear that Arindam Chatterjee sets his faith in quiet courage and perseverance, and a belief in one’s practice strengthened by healthy self-criticality. These works also suggest that the artist reposes a measure of trust in the unknown, unpredictable viewer who might become the <span “>sahridaya<span “>, the “heart-sharer” who reaches out and completes the work of art in her or his own receptive imagination.