ART AGAINST TERRORISM

TERRORISM AND THE ARTS

Terror, in the sense of a heightened fear, felt by a struck person or persons, caused by someone or something, are of two kinds: private and public. Terror of unknown and unknowable, and of irrationally perceived causative factors, such as gods, ghosts, darkness, depth, height, fire, forest, sky, water etc. are for psychologists, psychiatrists and psychotherapists to tackle. Although the privately felt terror do impact the arts, such as we find in the works of Richard Wagner, Edgar Allen Poe and Oskar Kokoschka, at this juncture of human history everyone in peaceful pursuit of life is concerned with unsuspected and sudden bursts of violence against lives and possessions, and messages of potential destructions those send out that benumb and make very large number of people apprehensive and anxious out of wits. Such violence is always perpetrated by a handful of angry, determined and obsessed persons who act secretly, till their action gets expressed in wanton destruction of lives (including their own) and possessions. The handful of obsessed persons who plan their action with utmost secrecy and direct their violence not only against whom they think as adversaries but, at times, also against those whose supposed grievances they supposedly take up for redressal. The terrorists, therefore, are those who secretly plan and surprisingly use utmost violence, mostly against defenceless targets in seeking compliance to their will (grievance redressal). Carrying any will, in public sphere, is a power proposition, ipso facto political. But apart from what the terrorists do, and what we call terrorism, there are other political events and politically motivated groups of people with different nomenclature using violence as a means of achieving the end. Wherein lie the difference?

Terrorism cannot be equated with rebellion, revolution and war, even though rebels, revolutionaries and combatants, like the terrorism& use violence as instrument for imposition of will.

Read MoreThe rebels, revolutionaries and combatants target bases, sources and points of power of the powerful adversaries, in order to destroy the power. Targets are specific and direct. The targets, that the terrorists strike at, are not specifically those that would make a dent in the power of the supposed adversaries. The targets, the terrorists strike at, can hardly ever be conceived as antithetical to their supposed cause. Their targets, most often than not, are soft targets, which leave power structure intact.

Terrorism makes a mockery of the lofty aims for which the activists indulge in misdirected violence. The terrorists, by their acts against defenceless endanger the lives, the labour and the dignity even of the people for whom they supposedly pawn their Lives. The rebels, revolutionaries and combatants, normally abhor striking at what and whom they do not consider as non-power targets, unless they resort to terrorism. In another respect also terrorism differs from rebellion, revolution and armed combat, insofar as the use of violence is considered. The secrecy in planning and the spatio-temporal surprise that must accompany terrorist violence are not integral to rebellion, revolution and war.

Lastly, and more significantly, the mentality with which terrorism has elevated a means of carrying political will it has become a faith or a credo that has vitiated their supposed end. With rebels, revolutionaries and armies’ violence remains only a means to achieve some professed aims.

Lately the much heard of phrase, ‘state terrorism’ so-called, is hardly even terrorism, although a state can be a very repressive state. One need not know his/her Thomas Hobbes that a state, whatever be the nature of the state, legitimately enjoys the power of coercion. A state often applies that legitimate power of coercion, on specific targets, at appointed time and place, without an element of surprise, and remains present for reaction. On the other hand, non-state elements with statist aspirations often secretly plan violence and carry out surprise strike which maybe equated with terrorism.

Terrorism, therefore is cowardice. Terrorists by their choice of time and place of use of surreptitious violence against the unsuspecting and defenceless non-adversaries are a scourge to normal pursuit of life and labour of all, including those for whom the terrorists supposedly speak. Terrorism not only threatens to wreck, and wrecks normal life activity without a promise of a constructive programme, it stifles normal life activities of all in the areas of their vengeful operations.

Even the most rebellious and revolutionaries among art activists desire to carry out their vocations peacefully, in a situation free from uncertainty and insecurity. The art activists hate to witness the destruction of fruits of their toil by bigots and philistines. The art activists, therefore, have to stand up and be counted among those who resolve to fight for the normalcy of life against insecurity. Security of life and solidarity of all forces against violence and uncertainty are the call of the hour.

AUTOIMMUNITY: REAL AND SYMBOLIC SUICIDES

Le 1 1 September or if we speak in another language, it is ‘September 11 but let’s not play the language game here. Since there was another strike in Mumbai dated 26/11, then, we have to speak in Marathi or Hindi if we accommodate the Derridian linguistic discourse. What is Autoimmunity? It is a process which is strange in behavior, where a living being, ‘in quasi-suicidal fashion, “itself” works to destroy its own protection, to immunize itself against its “own” immunity’.

9/11 as everybody says gives us the impression of a major world event. Why? Precisely for two reasons it can be considered as a major event:

that United States was targeted, hit, violated on its own soil for the first time since 1840 with high-tech knowledge, training and weapons supplied by America, and

the suicide attackers incorporate two suicides in one: Their own and by targeting the symbolic head of the prevailing world order. One could add another double to it, the WTC (the capital head of world capital) and Pentagon, the strategic military and administrative location of USA.

The terrorist attack of 26/11 in Mumbai was in a sense an attack against the principle of sovereignty that India has over its own land and as in America, we can notice the same design in targeting the Taj Hotel, its location and whom/what it represents. The only difference was choosing a small tenement where Jewish travellers used to stay which was targeted not by chance but for a deliberate purpose.

Before 26/11 India have witnessed several suicidal terrorist attacks in other places like J&K, Bangalore, Ahmadabad, Jaipur etc. What is interesting to me is that the event of 26/11 is the worst so far, almost terrible, terrifying, terrorizing: that is in and beyond territories. Hence, it signifies the demystification of the notion of the nation state, a rejection of the secular nationalistic ideal, a rejection of the idea of Hindu/Buddhist tolerance and coming of a new cosmopolitan order where citizenship is being extended into an Internationality of nation states. But the question which can be posed is that there is a limit of the citizenship of the nation state as well as that of the world state. The twenty first century is the time of disjuncture, otherwise, how does one forget the ‘positive and salutary role of the sovereignty of nation state’ which has in its constitution the moral, juridical and military right to protect the citizen’s right against the oppressive market, the intimidating power of the multinational capital as well as terrorist violence. And at the same time, it has a limiting/negating effect on a state whose borders are controlled and monopolizes violence through various forms/ techniques.

The stakes of violence which we have been witnessing for sometimes now are often territorial, ethnic, religious and so on. Have we become an intolerant society? What role does have tolerance now? Can we invoke Buddha, Gandhi, Tagore, Tolstoy, Voltaire, in this time of terror? Will tolerance an “appurtenance of humanity” collapse? Let me end by quoting Derrida:

“if intellectuals, writers, scholars, professors, artists and journalists do not, before all else stand up together against such violence, their abdication will be at once irresponsible and suicidal”.

TERROR – PRIVATE SPACES, PUBLIC NOTIONS

In March-April 2009, in the wake of the rising terror threat that is sweeping India and the world, nine galleries and initiatives across Kolkata came together to address the issue of “terrorism” – a word that is today defying definition, well exceeding the limits of ideology, politics, border, and nation to become a rampant global phenomenon.

In my attempt to contribute to Kolkata’s “Art against Terrorism” initiative in my capacity as a practising artist, I collaborated with the Counter-terror & Jungle Warfare College, Kanker and Akshar, Kolkata’s only ‘inclusive’ school. I shared images of the impact of terror and efforts to combat it with the schoolchildren. In the process, I encountered two vastly varying notions/understandings of “terrorism”. On the one hand, was a rigid definition where anti-establishment people’s movements that turned violent in their quest for rights and justice are branded “terrorist”, and are, therefore, “rightfully” quashed. On the other hand, from my interactions with the schoolchildren, I discovered that frightening misconceptions exist with regard to the definitions of ‘terror, terrorism and terrorists’ – in most cases, all of these are understood to be synonymous with Islam, despite the fact that in India alone there are voices of extremist dissent that belong to all religions. In all honesty, both notions chilled me to the bone and led me to question the definitions of “terrorism”, as have the nine artists featured in Gandhara Art Gallery’s contribution to the “Art against Terrorism” initiative.

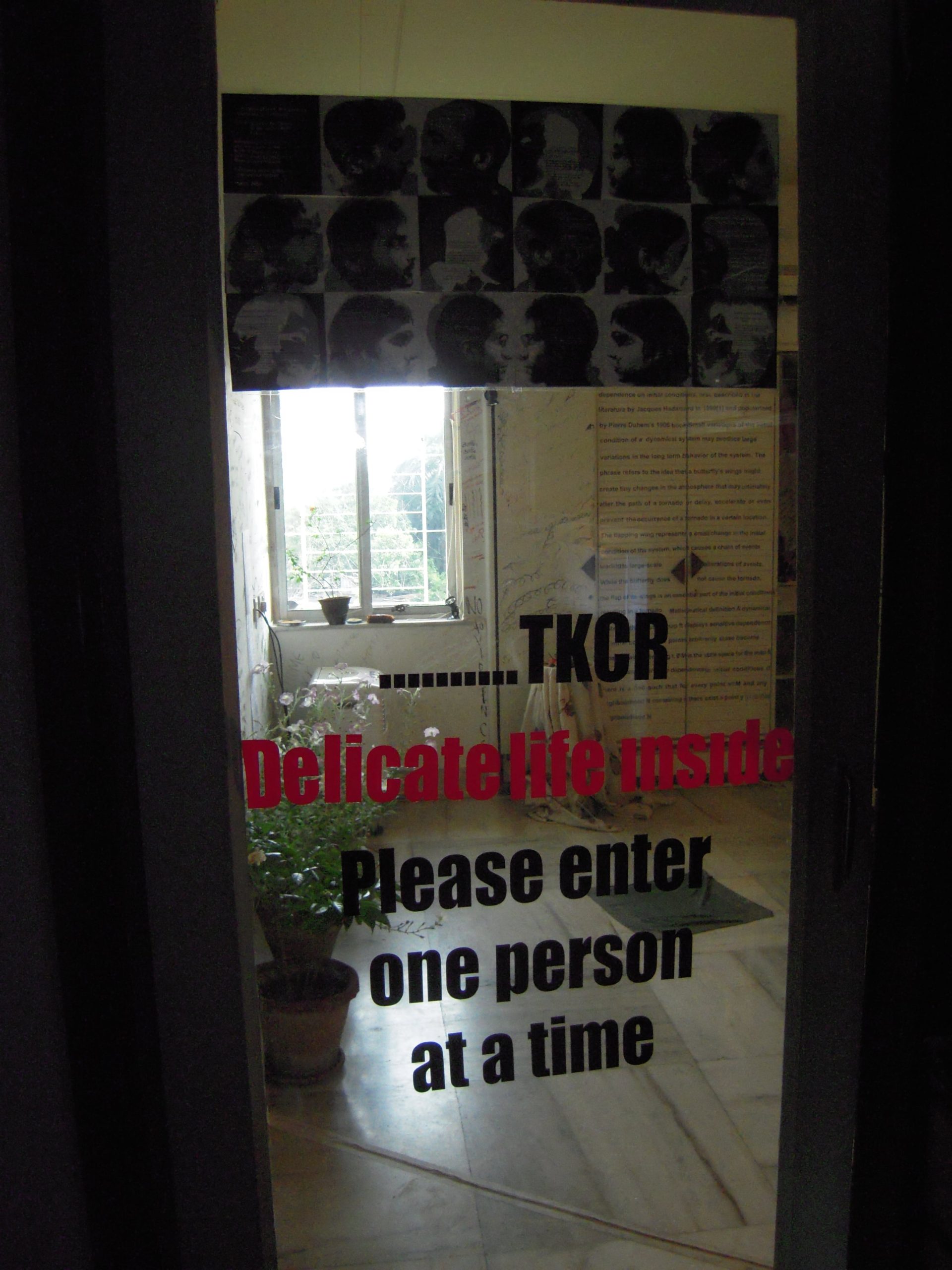

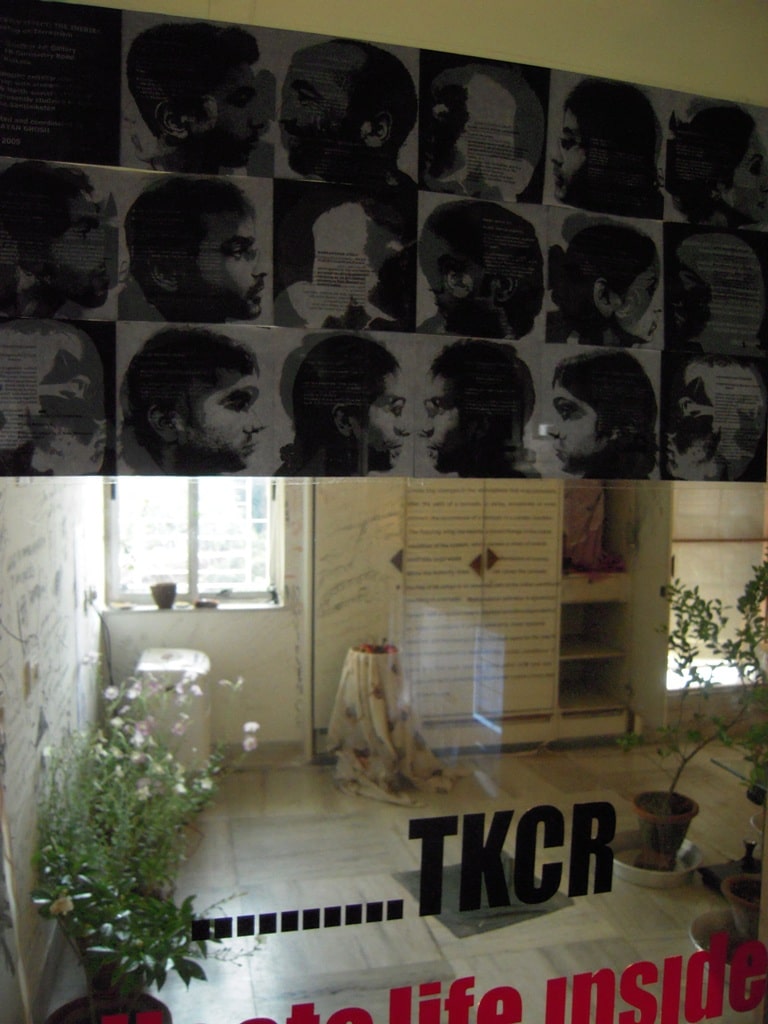

The Gandhara Art Gallery is housed in a two-bedroom apartment that continues to retain it’s identity as a place of residence. It’s limited confines that do not allow much room for escape, seemed rather appropriate a space in which to confront the current face of terrorism, slipping in through every nook and cranny in our lives, rendering the private space, normally seen as a space of security and comfort, no longer impervious to terror.

Adip Dutta takes his project, Juxtaposing the Vulnerable with the Secure, into the bedroom, perceived as the most personal and private of spaces. To enter this space of security, the viewer was required to undergo a body search, immediately subverting the security of both the space and the viewer to a position of vulnerability. Upon entry, the peace of what the artist perceives as “a space where one goes to rest at the end of the day” is invaded by a television screen that relentlessly beams ‘terror’ live into what is essentially a zone of comfort. By wrapping the furniture in the room, namely a bed and a rocking chair, with surgical bandage, the artist further heightens the sense of discomfort already created by the television broadcast. Disconcerting as it may seem, the viewer is invited to rest a moment on these bandaged edifices and contemplate a shrine on the window sill illuminated with fairy lights. Sepia photographs of departed souls stare out at you as you shift uneasily on your bandaged seat, contemplating what is no longer a bedroom, but a tomb or a memorial where rest is denied by the invasion of terror.

To add to the sense of unease, Debnath Basu contributed a wall-work to the bedroom. In stark black-and-white graphic imagery, the artist repeatedly delineates the dark figure of a human bomb with explosives strapped to the waist juxtaposed against a sea of Bengali text. The style of rendering the figure is reminiscent of athletic figures etched on ancient Greek vases, possibly a deliberate attempt by the artist to reference what is classically and unarguably heroic. The text in the background constitutes excerpts from an interview on terrorism in Iraq – a dialogue that discusses issues such as “counter-terrorism” and “state terrorism”. Clearly, the artist questions here the definitions of “terrorism”, the justification of countering what is perceived by the state as “terrorism”, and the terror that the state unleashes in its efforts to counter “terrorism”.

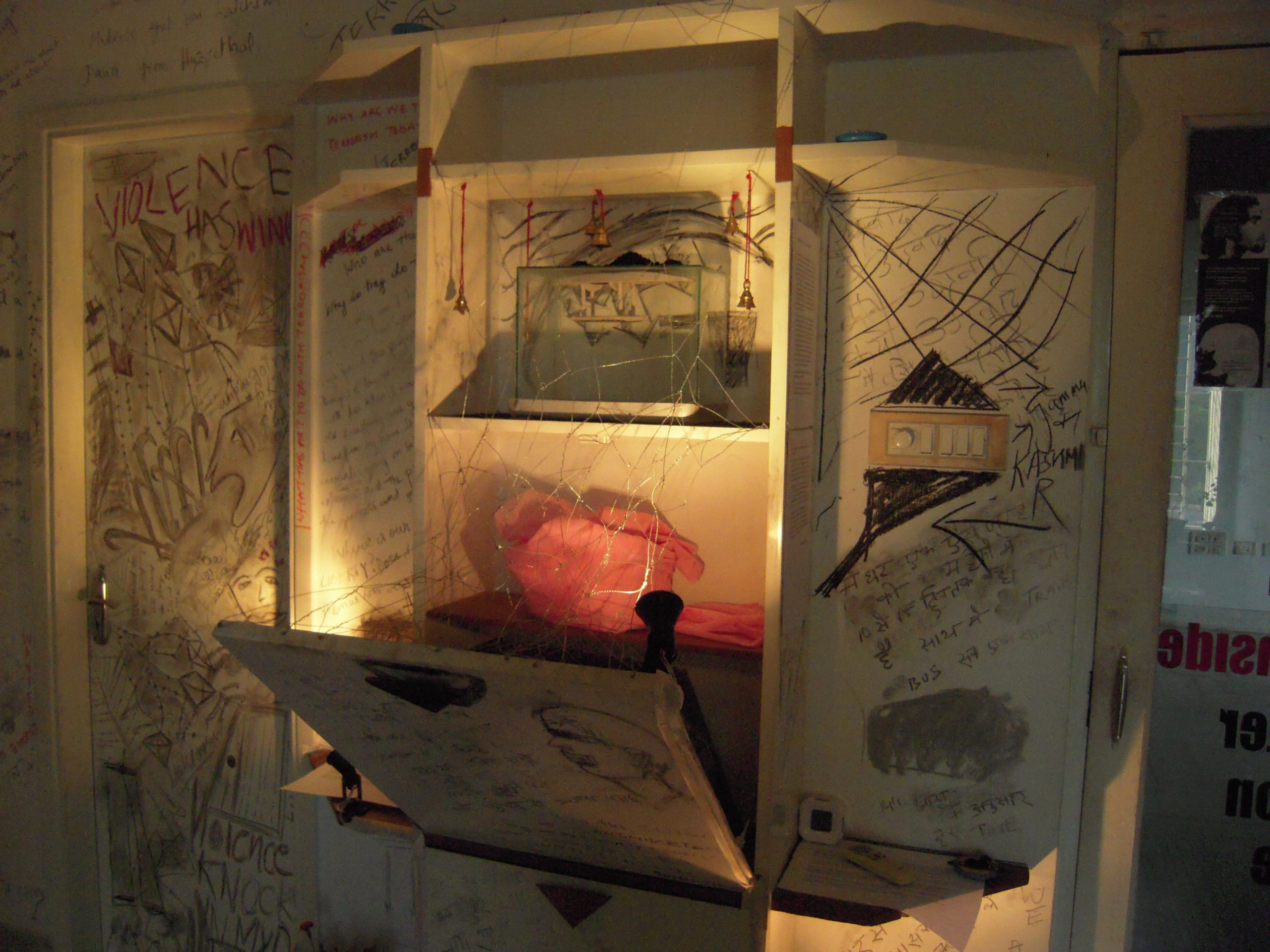

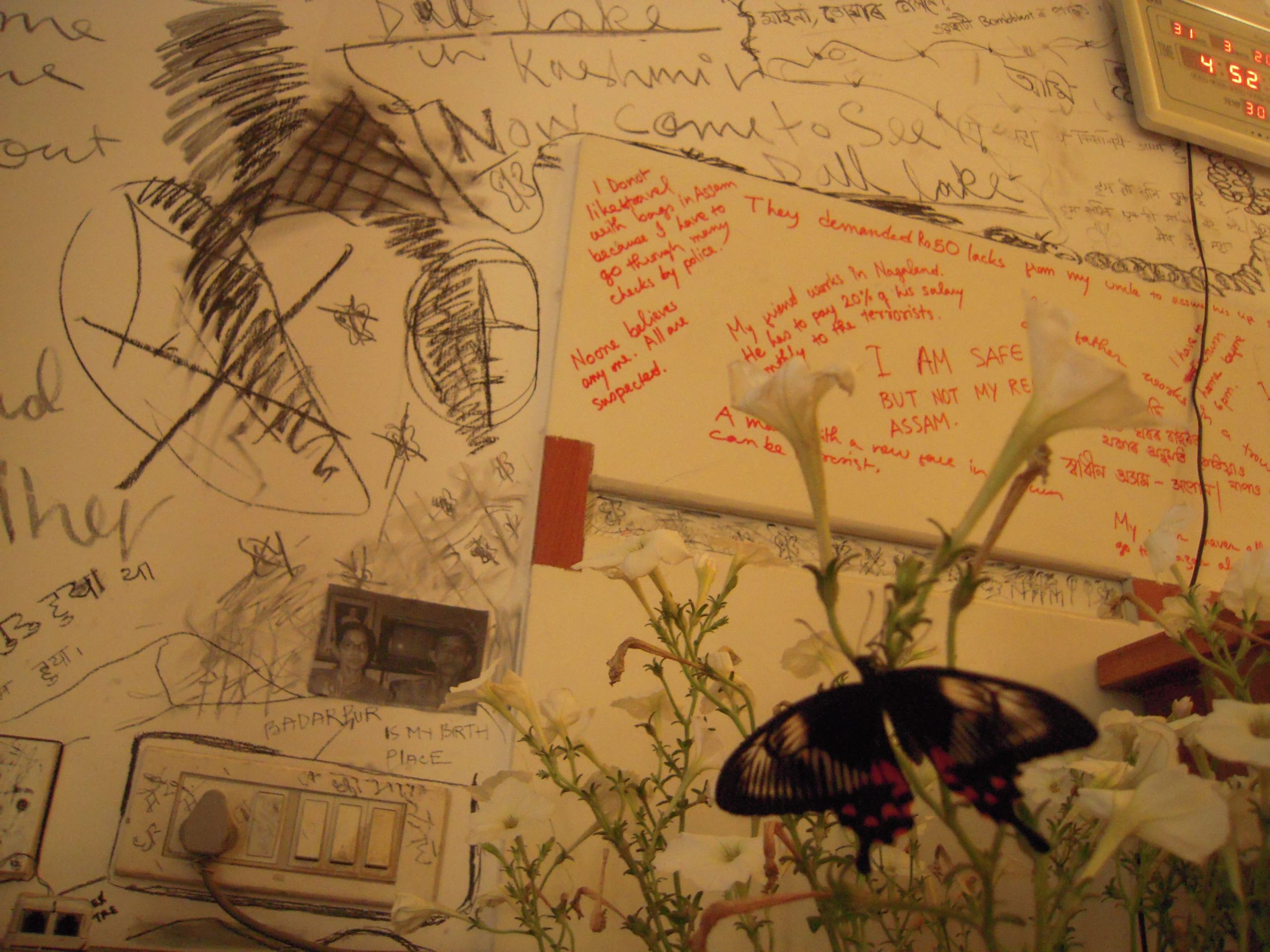

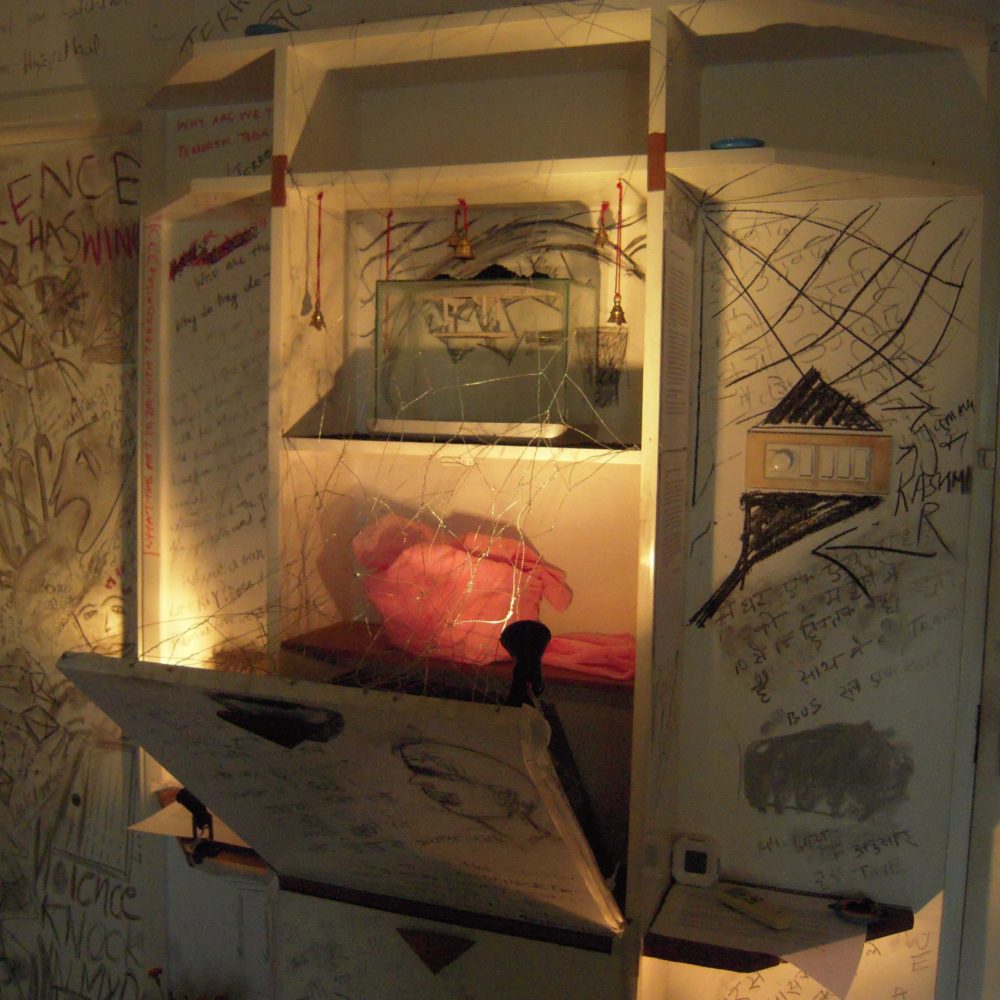

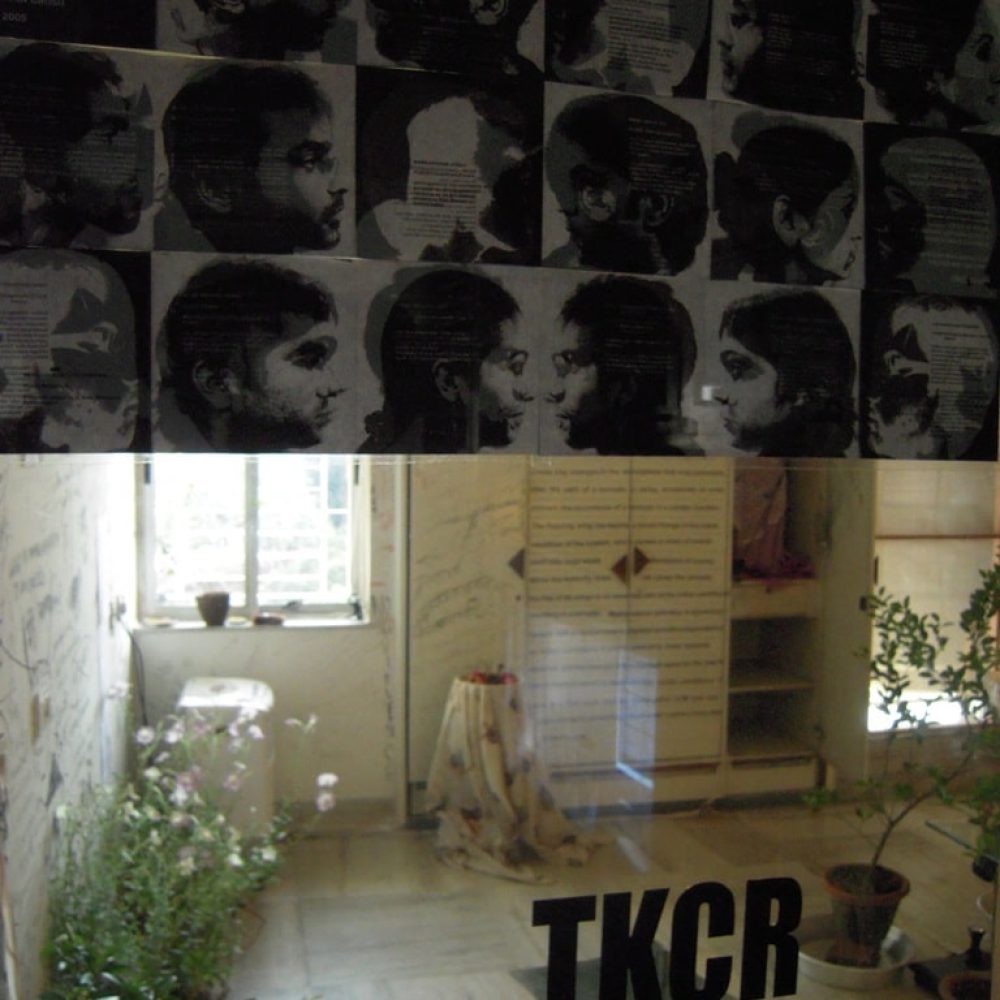

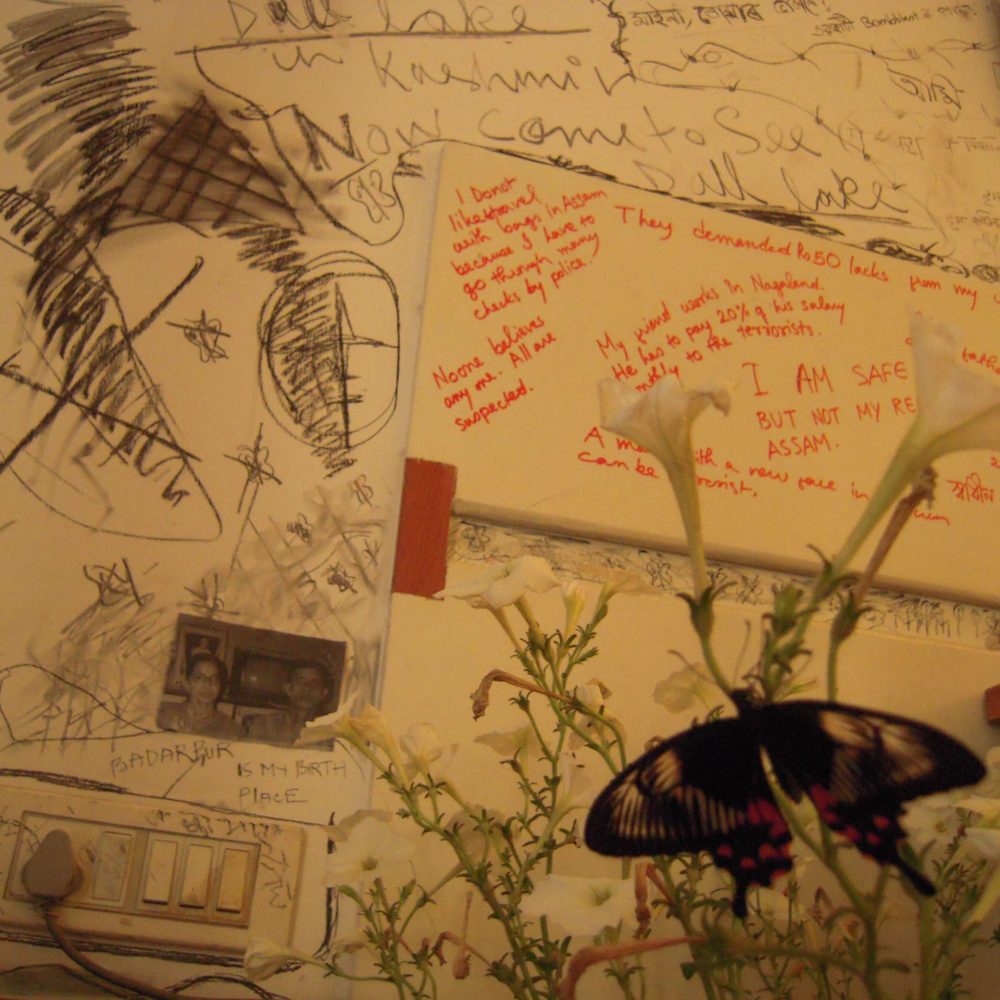

The second bedroom in the apartment was occupied by a site-specific intervention that Sanchayan Ghosh conducted with a group of students from the terror-torn north and north-eastern states of India. Butterfly Effect: The Interior transformed the bedroom into a workshop site where the students interacted and reflected upon their notions and private experiences of terrorism and violence. Consequently, this interior space was transformed into a claustrophobic site where the lifecycle of a butterfly was created in an artificial environment, attempting to cause what is known as the “butterfly effect” – the scientific phenomenon that the flapping of a butterfly‘s wings might create tiny changes in the atmosphere that may ultimately alter the path of a tornado or delay, accelerate or even prevent its occurrence. Video recordings of the proceedings of the workshop were projected within these artificial confines, graffiti pertaining to the student’s reflections covered the walls, and artifacts from the concerned states were displayed in vitreens. The ‘butterfly effect” attempts to draw a parallel with our inherited Colonial legacy – primarily the partitioning of the Subcontinent – in which lie the roots of many of the dissenting voices that are branded “terrorist” movements in India today. The flapping wing represents a small change in the initial condition of the system, which causes a chain of events leading to large-scale alterations of events. Just as the butterfly does not actually cause the tornado, the British did not actually cause the birth of terrorism in the Indian Subcontinent. But just as the flap of the butterfly’s wings is an essential part of the initial conditions resulting in a tornado, the divisive politics of Colonization are perhaps responsible for the violence and terror that keeps the Subcontinent in a ceaseless state of flux till date.

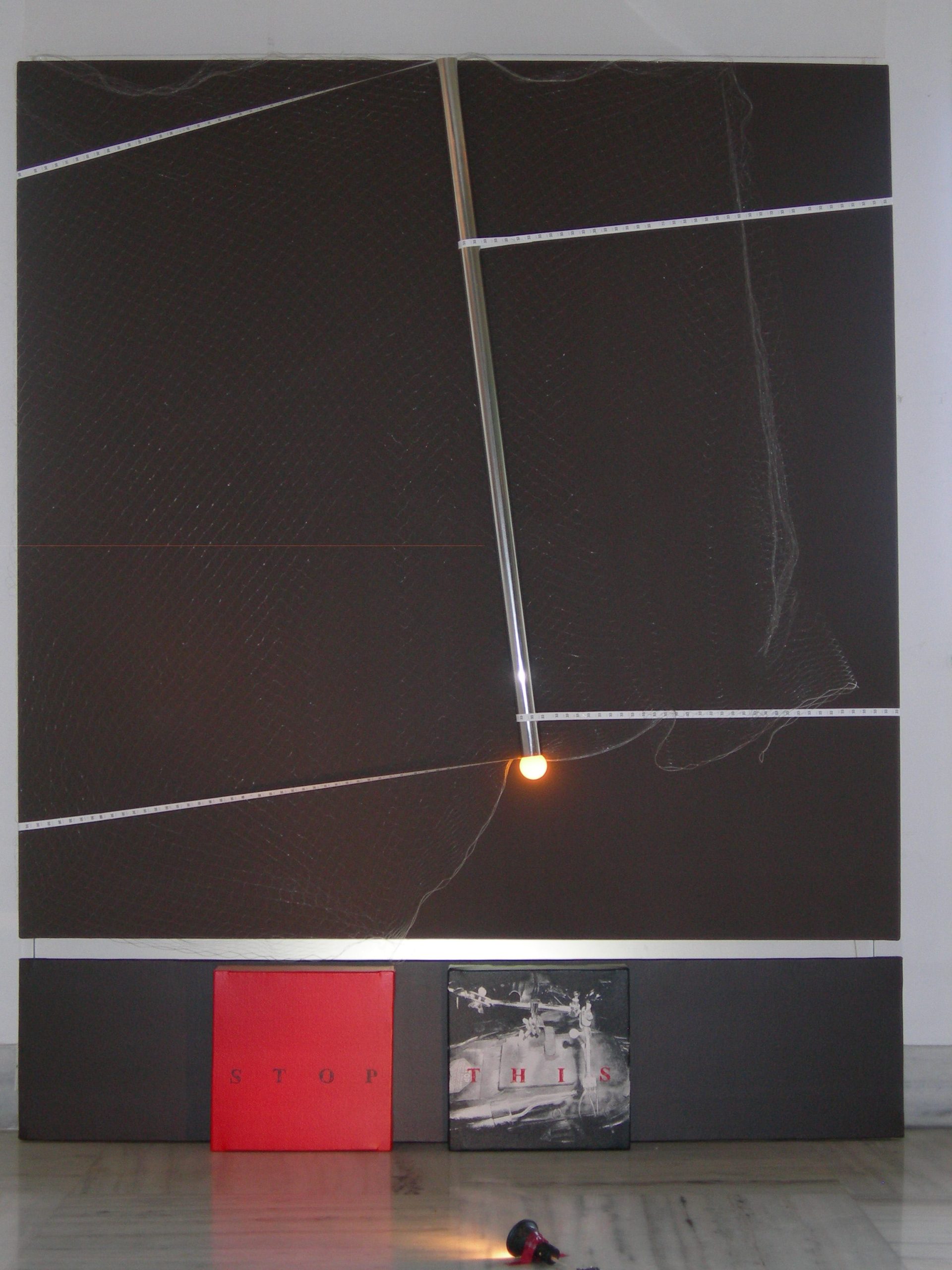

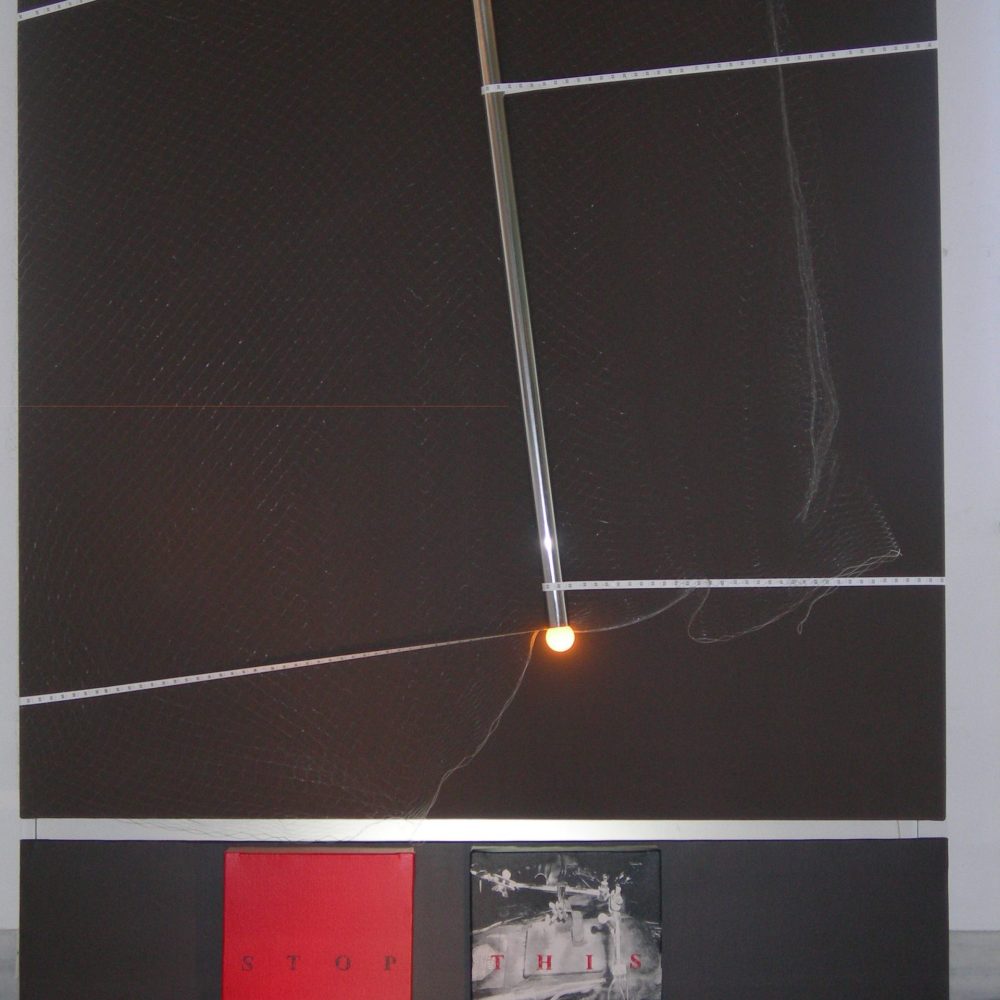

Epistle on a Splitting Image is a pristine work by Kazi Nasir accompanied by a violent verse by the artist himself. It laments the misnomers that breed terror, the self-destructive nature of terrorism itself, and the ceaseless cycle of violence that it perpetuates. Three box-like objects with images of the self and a leafless tree, each pierced through with the barrel of a gun, boomerang light off each other. The installation is disconcertingly silent, almost clinical in its rendering, belying the latent message of violence that is embedded within it.

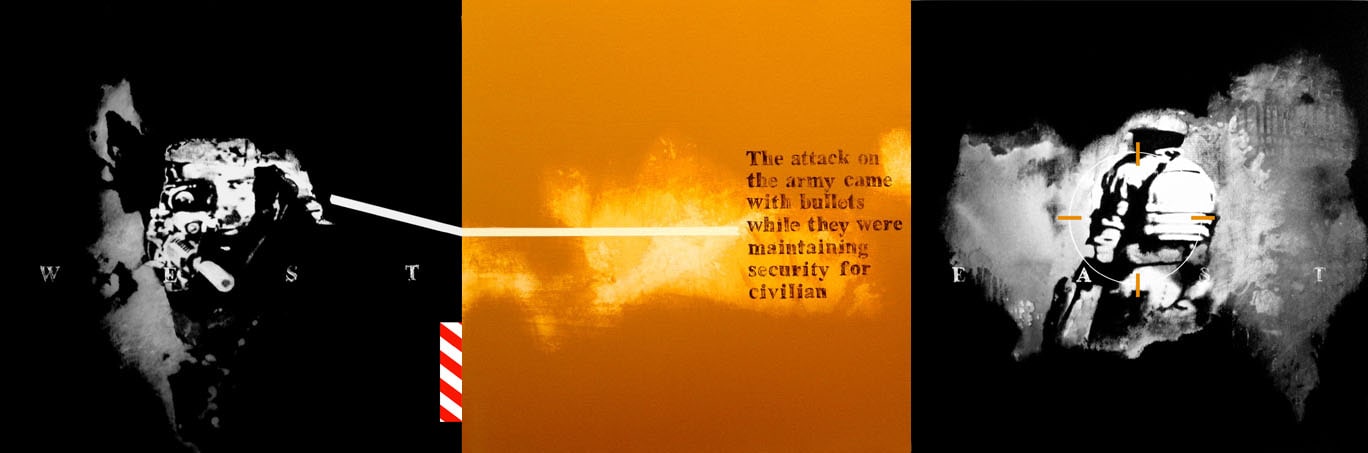

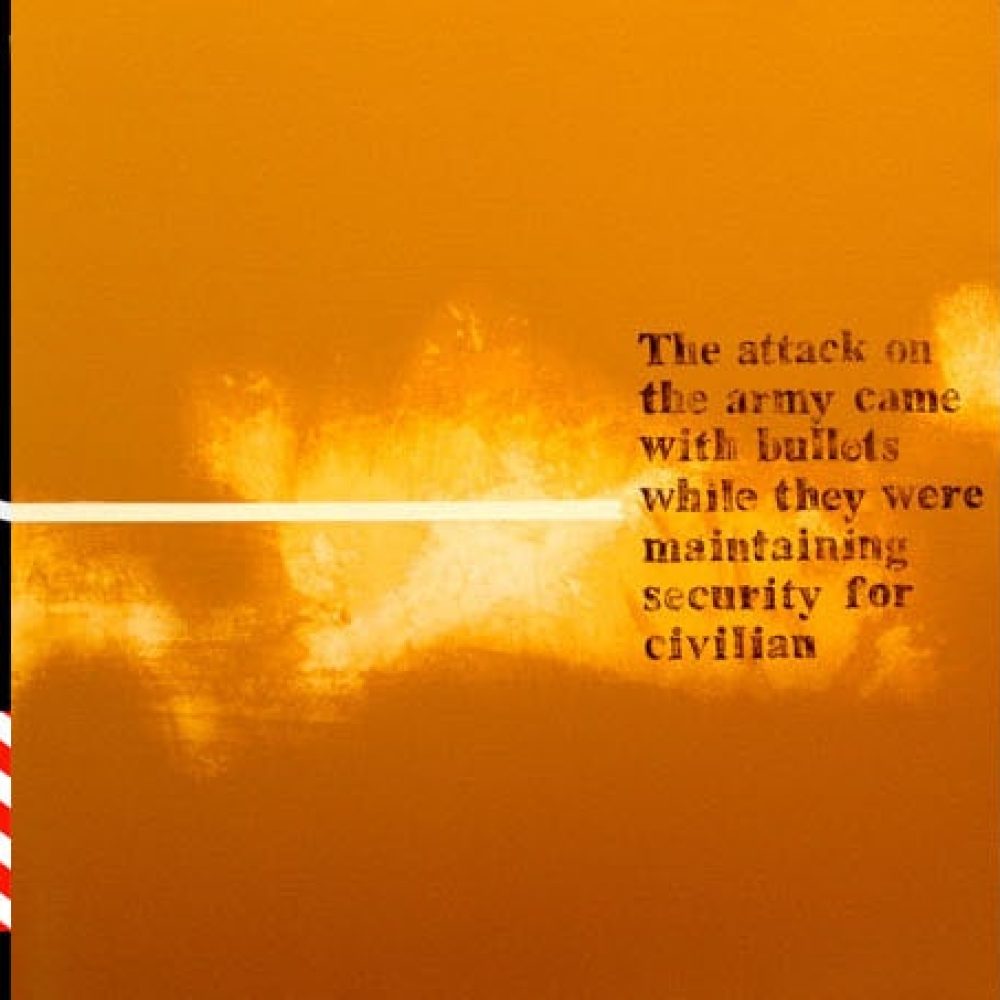

The print media habitually reports acts of terror with factual disassociation – on our part, as readers, we consume these snippets of news with an equivalent lack of involvement, until there comes a time when the act of terror comes home to us. Rathin Kanji’s painting Political Conflict appears to simulate just such a report – sensational yet dehumanised. His photorealistic imagery and customary graphic surfaces and colour palette defy all that is the humane as is often the practice of the media in the times in which we live. In contrast though, is the inclusion of a small snippet of text, which becomes in the final count the central humanising focus of the canvas – “The attack on the army came with bullets while they were maintaining security for civilians”.

Far removed from both Nasir and Kanji is Krishna Murari’s Engineered Flame, disturbing to an extreme. A life-size fibreglass figure of a youth, encased in a reeking animal hide, stands strapped to a vertically-placed trolley. His head is covered with a gas mask, and the whole is supported by an audio-video. This man-animal spells fear, violence, apprehension, and destruction, all strapped into a consummate, putrid, terrifying creature that signifies the human and inhuman rolled into a single aspect – the dichotomy that is terror.

Pradip Kumar Patra’s untitled torso is also an image of latent violence. The nude torso stands in a contemplative stance of apparent calm, arms akimbo. Above his decapitated throat spins a fan of five sickles, sharp as a razor’s edge. Though the sickles are still, contained within them is the ability to hurt and shed blood. The sickle, the world over and most particularly in Marxist Bengal, is seen as a symbol of the proletariat. In recent times, peasant uprisings in Bengal have shaken the very foundations of the ruling Marxist regime, thus causing many of them to be branded as “extremist” outfits. It is possible that the artist in his use of the sickle, references the power of the proletariat and the injustices that prompt it to raise a voice of dissent.

What prompts the making of a terrorist? Prabir Gupta raises this pertinent question in his sculptural work Testimony – “I had to feed my family”. Seated in a chair, as if at an inquisition, is a rather life-like mannequin, his lower body dressed in denim and office shoes. The torso, in contrast, is of stainless steel, comprised of the conical exhaust of a chimney, the shaft culminating into a tiffin carrier from which emerge two microphones. A miniscule ladder climbs the walls of the exhaust – the ladder to “success” according to the artist. Is the terrorist then a professional like any other, and terrorism a mere commodity to be bought and sold in a globalising market? And in this ongoing barter, does humanity simply evaporate like a whiff of smoke through the chimney exhaust? Is the terrorist ultimately a mere pawn in the political games that drive the institution of terror, simply trying to eke out a living like any other?

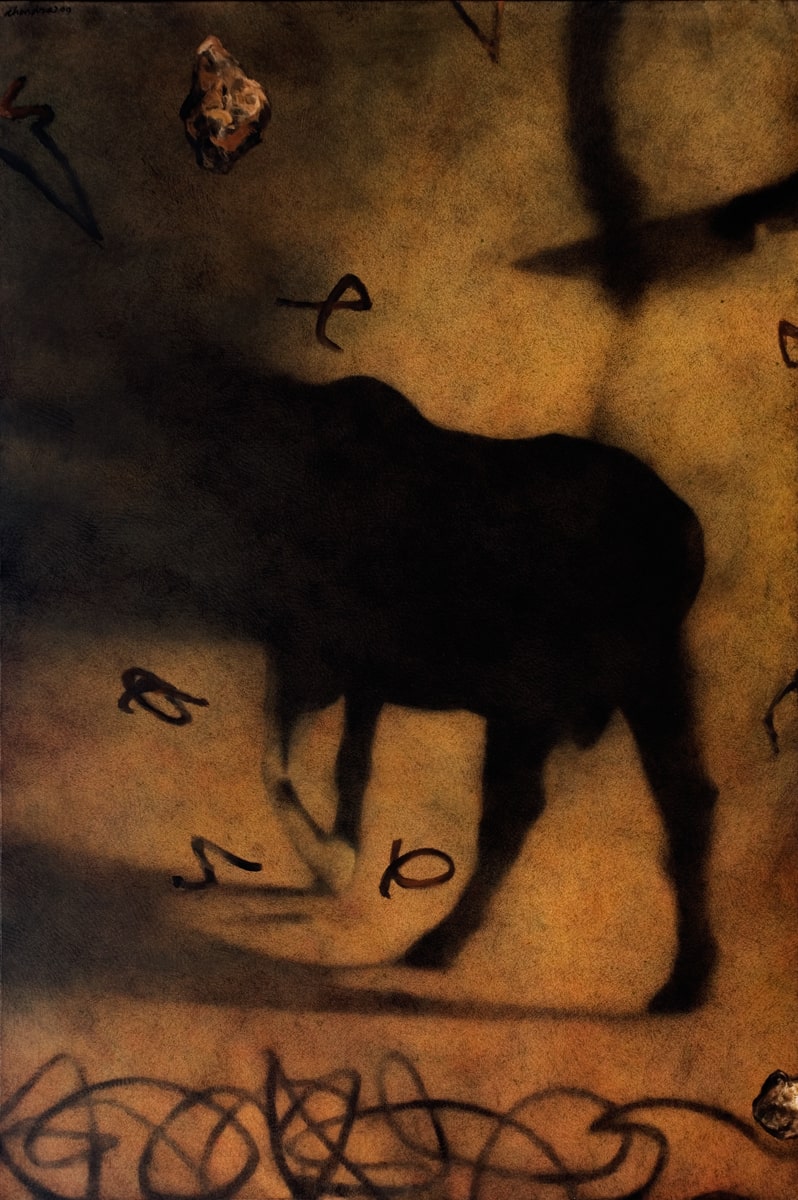

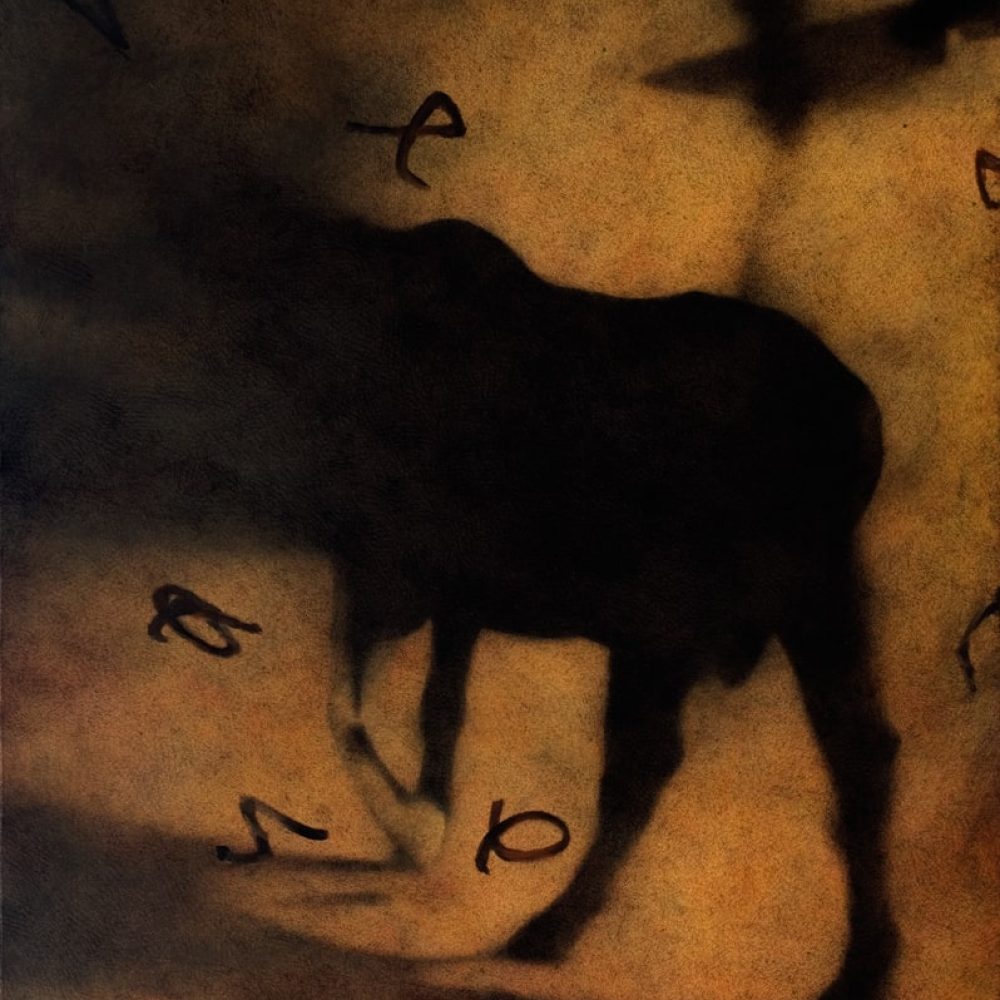

A ray of hope is visible in Chandra Bhattacharya’s untitled canvas of a bull. Though enveloped in dark smog in a terrain that is dusty and dead, the bull refuses to be vanquished, struggling instead to emerge from the darkness. The artist refers here to the dogged nature of the animal that tends to follow its cycle and its instincts despite all odds, unmoved by the forces that attempt to destabilise it, in the belief that the soot will eventually lift, the skies will be blue again, and it will find green grass.